By Kieran Brennan

•

January 28, 2026

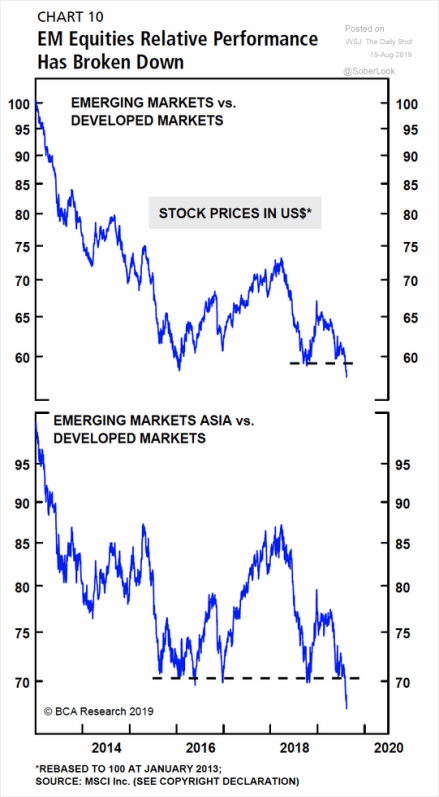

Dear Partners and Friends, PERFORMANCE K uroto Fund, L.P. appreciated +8.5% in the fourth quarter and finished the year up +64.9%. By comparison, the broad MSCI Emerging Markets Index rose +4.8% in the quarter, finishing the year up +34.4%. The positive contributors to Kuroto’s performance were broad-based, with 11 stocks contributing over $1 million of gains for the year and only 2 positions detracting more than $1 million. The biggest contributors to the performance were MTN Ghana, our Nigerian stocks, and Georgia Capital. The biggest detractors were Kosmos Energy and Gran Tierra. Looking at our portfolio today, we are surprised at how attractive it still looks given our performance last year. Our portfolio’s price to earnings ratio is 5.9x for 2026, with a dividend yield of 6%, generating an ROE of 28%. While these are imperfect metrics, they don’t show a portfolio that’s expensive. We take a more nuanced look at the valuation of our top five positions below, which represent 61% of the portfolio today. Moreover, we are still finding attractive incremental investment opportunities. In this regard, Brazil stands out as a particularly attractive incremental market for us. With policy rates at 15%, local investors are happy to hold fixed income securities which has kept equity valuations depressed. As concerns about US economic policy grow, risk capital should flow to emerging and frontier markets. US equities account for 47% of total equity value globally. Brazil, by contrast, accounts for just 0.6% of global equity value. Needless to say, a small shift from US equity markets to EM markets could result in a meaningful upward revaluation of emerging market stock markets such as Brazil’s. A breakdown of Kuroto Fund exposures can be found here . Investment Thesis Review for the Top Five Positions by Portfolio Weight MTN Ghana: 20.5% Portfolio Weight MTN Ghana continues to be our largest investment. Through the first nine months of 2025 (full year results are not yet released), the company’s revenue grew 36.2% and earnings were up 45.9%. It generated a ROE of over 50% and is on track to pay out 80% of earnings in dividends. The company continues to dominate the voice and data telecom services market, as well as money transfer and digital payments in the country. The biggest growth driver of the business has been data. Our understanding is that latent demand for data is such that any investment MTN Ghana makes into its telecom infrastructure is immediately utilized. MTN has not been under-investing in infrastructure, but its competitors have been. The second largest competitor was Vodacom, but they sold out to Telecel in 2023. Since purchasing Vodacom Ghana, Telecel has underinvested in its network and has been losing market share. The third and fourth largest networks, Bharti Airtel and Tigo, merged their operations in 2017 to attempt to compete more effectively, but they did not invest enough to be competitive and ended up selling to the government in 2021 for $1. Since then, the government has absorbed the third player’s operating losses while not investing meaningfully in infrastructure. Currently, the government is considering both selling a stake to remove ongoing losses as well merging its Airtel-Tigo with Telecel to create a stronger competitor to MTN Ghana. Combining two under-invested networks will not fix the problem unless someone commits to spending a meaningful amount of capital to add to and upgrade telecom infrastructure. MTN Ghana has invested over $3 billion to make its network the dominant one in the country. It’s unlikely someone will come forward to write a check big enough to meaningfully alter that dynamic. The second biggest growth driver, and potentially the most valuable piece of the business longer term is the mobile financial services business – MoMo. MTN continues to dominate money transfers and payments in the country with 90%+ market share. In early 2025, the government removed the e-levy tax on money transfer which spurred growth for the year. Now the service mix is shifting to higher value services like merchant payments and savings and lending products and away from pure person-to-person money transfer. The company recently separated its mobile financial services business from its telecom business internally, and going forward will report the financials of these businesses independently. The company is guiding that in 3-5 years they will list the mobile financial services business separately. It’s possible that this leads to a higher valuation for the group at some point, as these sorts of fintech businesses tend to trade at much higher multiples than telecom businesses. In our estimates, we see the stock currently trading at 5.6x our estimate of 2026 earnings, earning a 55% ROE and paying out a 10.7% dividend yield. The company forecasts high-30s% revenue growth in the medium term, stable margins, and a continued 80%+ payout ratio. Georgia Capital: 12.2% Portfolio Weight Georgia Capital had a great year. From December 2024 to the end of Q3 2025, the company’s NAV per share increased 42%. And for the full year 2025, the company is forecasting a 46% increase in FCF per share. The share price outpaced the intrinsic value growth, and the discount to the sum of the parts that the stock trades at has come in from ~50% discount at year end 2024 to a ~25% discount today. There were three big drivers of Georgia Capital’s performance in 2025. The first was the strong performance of its largest holding, Lion Finance Group (formerly known as the Bank of Georgia). Since 2019, when current CEO Archil Gachechiladze took over, Lion Finance Group has transformed from a good bank into a great one. The ROE expectation has increased from low-20s% to high 20s%, Net Promoter Score has increased from mid-30s to mid-70s, and 2025 EPS is forecast to be nearly 5x what it was in 2019. In 2025, the bank continued to perform strongly and is now getting recognized for it in the stock market. Listed in London, it is now a FTSE 100 stock, and having had traded around 1x book value for the past 5 years, is now at closer to 1.5x Price to Book Value. We think the bank will continue to grow revenues at a double-digit percentage, earn a high 20s% ROE, and support a 5%+ dividend yield. As such, we think Lion Finance Group stock still trades at a very reasonable valuation, and are comfortable with it as just over half of Georgia Capital’s NAV. The second big driver for Georgia Capital in 2025 was its aggressive share repurchase program. Since merging with its healthcare subsidiary in August 2020, Georgia Capital has shrunk its share count from 47.9 million shares to 35.4 million at the end of Q3 2025. From Q1 through Q3 this year, they repurchased 10.4% of their beginning of 2025 shares outstanding and continued to buyback through Q4. They funded this aggressive buyback through a combination of operating cash flow, selling down some of the group’s stake in the bank, and disposing of some non-core assets. Repurchasing shares while trading at a substantial discount to NAV is a good recipe for NAV per share growth, and Georgia Capital did a lot of that this year. Now that the discount has closed to a ~25% discount, this is less attractive but still reasonable given that look-through valuation is still only a single digit P/E multiple. The third key 2025 driver for Georgia Capital was the increase in value of the rest of Georgia Capital’s portfolio. The biggest pieces of the group after the bank are its pharmacy business, hospital business, and insurance company. Pharmacy and hospitals saw a 21.1% and 38.7% increase in operating cash flow respectively, and insurance saw a 23% increase in profit before tax. We expect continued double-digit profit growth in the medium term for these businesses, though not 20%+, which was helped by a cyclical margin recovery in 2025. Currently, our look-through P/E multiple for the group is 7x, which is attractive for this combination of businesses that earn good returns on capital and grow earnings double digits. Going forward, we anticipate growth will be driven more by earnings growth and capital returns rather than a decrease in the holding company discount to the sum of the parts. As such, we’ve trimmed the position modestly. Seplat Energy: 12.2% Portfolio Weight Seplat acquired Exxon Mobil’s shallow water operating unit in December 2024, more than doubling the size of its production and reserves. As a result, 2025 was a year of asset integration. Thus far, the company has managed the much larger production base well. Production averaged 135,000 barrels of oil equivalent per day (boepd) in the first three quarters of 2025, up from less than 50,000 boepd prior to the acquisition. Seplat has maintained this level of production throughout the year without drilling any incremental wells into the former Exxon Mobil assets, only reactivating old, previously shut-in wells. In fall of 2025, Seplat unveiled their 5-year plan for the newly combined portfolio. Encouragingly, Seplat was able to keep most of the Exxon Mobil in-country team, many of whom have 20+ years of experience with these assets and were trained to Exxon’s global standards. This makes the five-year plan to grow corporate production from 130,000 boepd to 200,000 boepd look very achievable. Seplat is trading at a high single digit FCF yield at the current low-$60 oil price. Debt to cash flow is less than 1x. They plan to pay out 45% of FCF as dividends while also investing to grow production approximately 9% per year for the next 5 years. Assuming a $65 Brent oil price, Seplat is guiding for a cumulative $2 to $3 billion in FCF over the next 5 years, which compares to their equity market cap of $2.5 billion. By 2030, Seplat should be producing over 200,000 boepd, generating north of $500 million in FCF annually and still have a long growth runway ahead. That said, it is no longer as enormous of an outlier in terms of valuation relative to some other emerging market oil and gas ideas we have, two of which are trading at north of 20% free cash flow yield today or in the next six months. Solidcore Resources: 11.8% Portfolio Weight In 2025, Solidcore made significant progress towards cutting its remaining ties to Russia. Notably, they bought back all the shares held in Russian depository and meaningfully advanced the construction of their new Kazakhstan-based POX plant. With the completion of the Russian share buyback on December 19th, 2025, Solidcore ended a multi-year standoff with Euroclear and created a path to reinstating their dividend. With respect to the POX plant, Solidcore successfully transported their new 1,100-ton autoclave manufactured in Belgium to site in Ertis, Kazakhstan, which was a year-long, technically demanding logistics operation. It required night-time transportation, reinforced roads, and careful coordination to avoid disrupting city life. With the autoclave now in place, the project has begun to ramp full-scale POX construction. We believe the new POX plant could be up and running by year-end 2027, at which point we would expect Solidcore to re-list their stock on the London Stock Exchange. CEO Vitaly Nesis is working to put in place a world-class board and, along with an LSE-listing, recapture the premium valuation that Polymetal garnered prior to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. It is not often that a CEO gets to build the same company twice, but we think that will be the case for Vitaly Nesis and Solidcore. The scale of the revaluation opportunity for Solidcore remains mouthwatering. With a current market cap of $3.5 billion, net cash of $1 billion, and annual free cash flow of $1 billion, Solidcore trades at a 2.5x Enterprise Value to FCF (EV/FCF) multiple. Similarly sized peers typically trade at a 10x EV/FCF multiple or more. We think the dividend will be an initial catalyst for revaluation, and the ultimate revaluation will occur when the equity re-lists on the LSE. Guaranty Trust: 8.9% Portfolio Weight Guaranty Trust performed well in 2025, posting a 31% ROE while growing their loan book by 16%. Earnings per share declined 6% YoY due to the normalization of their foreign currency earnings (rather than any deterioration in the business). After a lost decade under the former President Buhari, Nigeria is now beginning to grow again. GDP grew at 4% in 2025 despite weak oil prices, and government foreign exchange reserves are again healthy. Where inflation ran at 25% a year ago, it dropped to 14.5% as of November 2025. We expect Nigerian interest rates to follow inflation lower, which should spur loan growth. For the first time we can remember, Nigerian businesses are borrowing and investing, the currency has been stable, and the locals we speak to are genuinely optimistic. With a capital ratio of over 40% and a loan-to-deposit ratio of only 27%, Guaranty Trust remains Nigeria’s most conservative bank. With a cost of funding of only 3% and a cost to income ratio of sub-30%, Guaranty Trust doesn’t have to take much credit risk to generate spectacular returns on equity. Not surprisingly, simply owning government bonds is their preferred strategy in the current rate environment. Today, Guaranty Trust trades at 3.3x forward earnings and just less than book value. We expect the company to continue earning at least a high-20s% ROE, which should support both a 10%+ dividend yield and strong loan growth. Sincerely, Sean Fieler & Brad Virbitsky