Kuroto Fund, L.P. - Q1 2013 Letter

Dear Partners and Friends,

PERFORMANCE & PORTFOLIO

Kuroto Fund rose +1.7% in the quarter ended March 31,

2013. Over the same period, the MSCI Asia Pacific Index was up +5.6%. Through May 31, 2013, we estimate the fund was up +6.6% while the MSCI Asia Pacific rose +5.5%.

“Abenomics”: Japan’s Faux Prosperity Initiative

“There is new oxygen in the air,” is the oft-repeated refrain we’ve been hearing thanks to the radical macroeconomic policies of Japan’s recently elected Abe administration. Japanese and foreign equity investors alike seem to have experienced a bout of excessive optimism as a result of the risky Nipponese experiment in accelerated money printing. After decades of liquidation, Japanese stocks suddenly have come to life with everyone from Goldman Sachs to Nikko Securities (which announced aggressive new openings of brokerage offices) jumping on the bullish bandwagon.

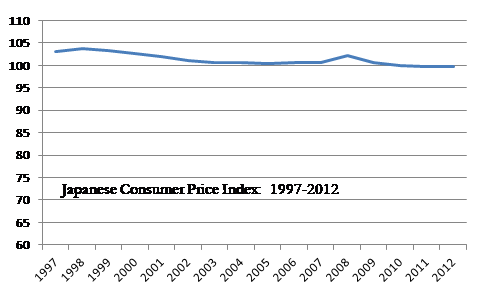

Color Kuroto skeptical. We have been sellers of our Japanese stocks so far this year. Since January, our weighting in Japanese equities has declined from 9% to 4%. For starters, we take exception to the proposition that Japan’s recent decade and a half of very modest deflation is the source of its economic problems. Not only does Japan’s deflation look more like price stability (see graph below), but deflation need not be synonymous with economic malaise. After all, America’s economy grew rapidly, despite serious deflation, in the late 19th century. Hence, we doubt the new Bank of Japan’s (BoJ) radical and dangerous reflationary policies will fulfill the current high expectations.

Yen debasement has, however, led to a dramatic rally in Japanese stocks which are up roughly 50% in Yen terms, despite the recent dip, since the rally began in November of last year. Sustaining this rally, however, will prove difficult if quantitative easing does nothing to address the country’s underlying structural problem. Moreover, adding still more deficit spending to already massive government liabilities—besides further depreciating the nation’s already shaky credit—similarly misses the real issues. In fact, by providing false hope of a painless solution, Prime Minister Abe’s extreme policies actually work against structural reform, the essential “third arrow” of “Abenomics.”

“Yes, everyone agrees, some reforms are needed,” argues Michael Porter in his industry-by-industry study of the Japanese economy’s failures in the 1990s. However, there is a lack of consensus as to the extent of reform needed since, as Porter presciently wrote in 2000, “…most believe the economic engine is basically sound, if only the government would jump start it with a massive dose of credit and demand stimulation.” This consensus view is wrong in Porter’s estimation. Instead, he argues that the essence of “…what ails Japan goes beyond macroeconomics. Japan’s problem is rooted in microeconomics, in how the nation competes industry by industry.”[1]

Kuroto’s view, developed from meeting with hundreds of Japanese managements, is consistent with Porter’s. Specifically, we contend that deeply entrenched Japanese business practices remain the real obstacle to growth. In particular, Japanese businesses’ lack of focus on return on capital employed, as demonstrated by their long history of very low returns on assets (ROA), must be addressed if Japan is to resume its progress. Porter accurately observes, “…Japanese corporate profit rates have long been chronically low by international standards, even in [globally] competitive industries and even after controlling for accounting differences.”[2]

Porter’s observations notwithstanding, the Japanese stock market’s performance seems to be a derivative of the prevailing optimistic view on Japan. For example, a spring Macquarie Economics report cites Japan’s very high scores in their “World Management Survey,” corresponding to their “extended bull market forecast.” Macquarie even goes so far as to praise Japanese management quality—pointing out that in their survey, Japan ranked second to the U.S. in “average management scores” and excelled in such qualities as “innovation” and “process sophistication.”[3] While we too are impressed with Japanese “process sophistication” in the manufacturing sector, the generally abysmal returns on capital employed raises questions about the overall quality of Japanese management. Japanese companies have averaged just a 1% ROA over the past three decades.[4] This compares with an 8% average ROA for US companies over the last fifteen years (see Q4 2011 Letter for more on Japanese “returns”).[5]

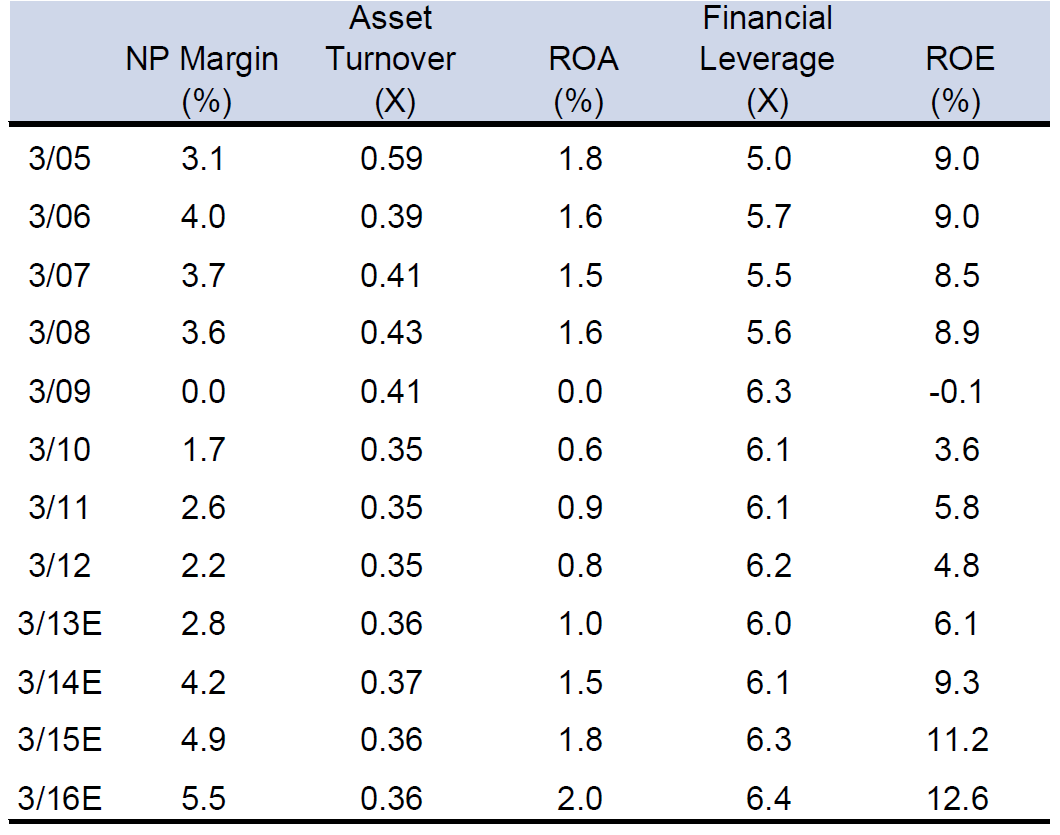

Goldman Sachs also paints an upbeat scenario by directly confronting the inadequate return on investment issue in their recent “BoJ Regime Shift” report. Goldman cites “corporate reforms” such as, “leaner cost structures, higher overseas sales exposures, and scope for cash deployment” as factors that will improve the corporate profitability in Japan. But, a glance at Goldman Sachs’ own estimates show ROA barely reaching the still very depressed 2% level by 2016—hardly a reason to believe the country has turned a major profitability corner. In the same report, Goldman actually notes that corporate Japan would need to triple their net profit margins before they could equal the rest of the developed world in capital efficiency.[6]

In our opinion, for Japan to enjoy sustained prosperity, corporate Japan must become more accountable for the efficient use of capital. Consensus decision making and the close relationships between management and labor, suppliers and producers (e.g. cross shareholdings), and government and business has excessively eroded management accountability. This severe blurring of the lines of responsibility has allowed Japanese managements to defer painful decisions needed to drive higher capital returns. Moreover, the lack of a market for corporate control in Japan makes changing this engrained corporate mismanagement a tall order.

Shareholders, unfortunately, have simply not been in a position to improve the Japanese corporate status quo. Maybe Third Point’s Daniel Loeb will succeed where so many others have failed, holding Sony Corporation’s management to account for improving their stock performance (the company had lost money for four years before posting slight positive earnings in fiscal year 2013 with a corresponding 2% ROE). If Loeb’s activism represents the onset of a real market for corporate control in Japan—one that encourages widespread reform in Japan’s corporate board rooms—Kuroto will reconsider our skepticism about the prospects for transformational economic change. To be clear, Japan needs more than an independent director or two. To quote Porter again, “Japan needs a new corporate governance system… Without the pressure to use capital efficiently and earn decent profitability, Japanese companies will not address their fundamental competitiveness problems. ”[7]

Worst of all, rather than address these historic and difficult structural issues with the help of market forces, the newest bout of hyper-quantitative easing and even more fiscal stimulus strikes us as one more effort to suppress market forces. To the extent money printing works as advertised, Japan will get a little inflation and a little growth, but we are unlikely to see much change in corporate Japan. To the extent that the new policy initiatives of extreme macro-stimulus overshoot and the country debases into hyperinflation and/or government credit crisis, we may finally get real change in Japan. While this catastrophic “financial Fukushima” scenario would probably produce sweeping national reform, it is most assuredly not a reason to become enthusiastic about Japanese stocks today. Accordingly, we are sitting out this rally. We remain convinced that Kuroto’s lopsided risk/reward exposure to Japan on the short side, via Japanese Government Bond interest rate swaps, will ultimately prove an outstanding investment.

Sincerely,

Andrew Ewert

Sean Fieler

Daniel Gittes

William W. Strong

ENDNOTES

[1] Michael E. Porter, Can Japan Compete?, 2000, p.1-2.

[2] Michael E. Porter, Can Japan Compete?, 2000, p.4.

[3] Macquarie Economics Research, Japan and the USA: Profiting from good management. March 21, 2013.

[4] SMBC NIKKO. This analysis includes ~30,000 companies, excluding financial companies, from 1981-2010.

[5] Bloomberg, average ROA of S&P 500 companies

[6] Kathy Matsui, et al., BoJ Regime Shift, Goldman Sachs Global Economics, April 11, 2013.

[7] Michael E. Porter, Can Japan Compete?, 2000, p.151.