Equinox Partners, L.P. - Q1 2013 Letter

Dear Partners and Friends,

PERFORMANCE & PORTFOLIO

Equinox Partners declined -0.6% in the quarter ended March 31, 2013. For the year to date through May 31, 2013, the fund was down -3.0%.[1]

Long-Term Performance

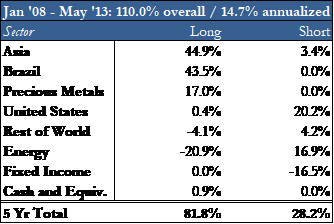

Equinox thinks about investments over a very long time horizon and tolerates volatility in pursuit of superior long-term returns. This orientation translates into an average 4-5 year holding period. The table below presents our overall and annualized performance since January 2008 and highlights the key contributors/detractors by sector.[2]

Portfolio

Through May 31, the shares of our gold and silver mining companies were down -22% for the year. This decline compares favorably with the -38% decline in the mining index over the same period and has been largely offset by the positive performance of our other holdings. [3]

For the better part of a year, we have been net sellers of fully-valued Southeast Asian and Brazilian companies. We’ve redeployed the capital generated into superior operating companies in Peru, Eastern Europe, the Middle East, the U.K., and even the U.S. As a result, our ‘Rest of the World’ allocation (ex-U.S. position) has risen to 21% of partners’ capital from 13% at the beginning of the year.

With gold prices lower and fundamentals unchanged, the last few months have presented opportunities to add to our extremely-undervalued, highly-economic gold & silver miners—thereby keeping our exposure constant at roughly a third of partners’ capital. These mining positions, in combination with our better businesses and low-yielding sovereign debt shorts, position us well in an over-indebted world dependent upon negative real rates.

Brazil

Over the past year, we’ve been persistent sellers of our superior Brazilian businesses, taking our Brazilian exposure from 22% of partners’ capital at the beginning of 2012 to just 6% at the end of May. While we remain enthusiastic about Brazil’s best entrepreneurs, we are less enthusiastic about the valuations of their businesses in the stock market and we are increasingly concerned about the inflationary forces growing in Brazil.

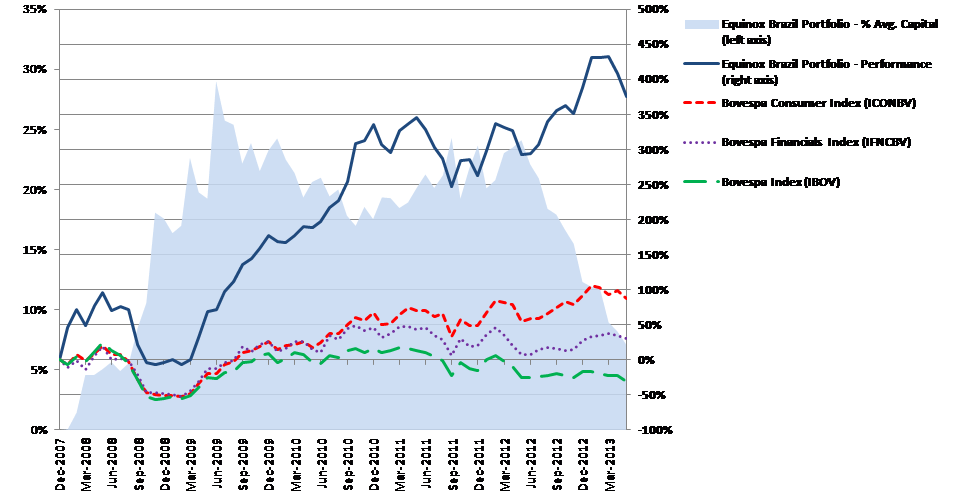

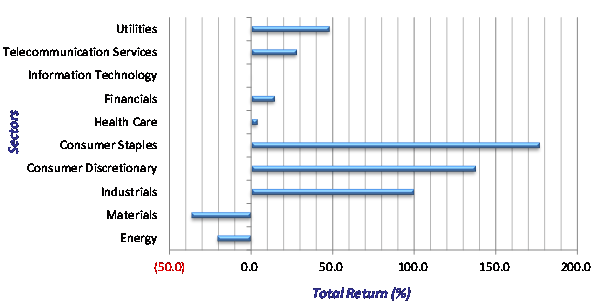

The value of our Brazilian holdings has risen +375% since our first purchase in 2008 despite the fact that Brazil’s Bovespa Index was down -30% over the same period. Declining commodity companies have weighed heavily on the Bovespa’s performance in recent years while the non-commodity companies on which we have focused have done extraordinarily well.

Higher valuations and deteriorating macroeconomic discipline have combined to make Brazil a less attractive investment location. Specifically, we are disappointed with President Dilma Rousseff’s decision to micromanage private-sector prices and to blatantly politicize Brazil’s central bank. Her actions have effectively terminated the tacit agreement between the Brazilian elite and former president Luiz Lula da Silva that governed Brazil for most of the past decade.

Having lost three consecutive presidential elections, Lula opted for a different strategy for his fourth run in 2002. While still a populist, he symbolically traded in his Che Guevara t-shirt for a suit. He courted business leaders by putting Antonio Palocci—a moderate early member of the Workers’ Party—in charge of his economic team. Furthermore, he promised to work to keep deficits down and to not politicize the central bank—promises he delivered on by keeping spending in check and by the appointment of Henrique Meirelles to head the central bank. Meirelles, one of our favorite central bankers in recent times, never left any doubt regarding his focus on bank solvency and low inflation.

Unfortunately, Lula’s eight years of benign rule and corresponding popularity freed current president Dilma Rousseff from having to make any of the same pledges. In fact, from the outset, Rousseff made clear she would not follow in Lula’s hands-off approach to monetary policy. Rousseff’s pick to head Brazil’s central bank, Alexandre Tombini, had none of the credibility of his predecessors, Arminio Fraga and Henrique Meirelles. Prior to their respective appointments, each had senior roles in the private sector: Fraga at Soros Fund Management and Meirelles as president of BankBoston. Tombini, by contrast, had never ventured beyond the government and the academy.

An article in one of Brazil’s leading newspapers, Estado do Sao Paulo, entitled “The Domesticated Central Bank” captures the dynamic perfectly: “…there can be no doubt about the influence of President Dilma Rousseff in the official policy rate, the main instrument of monetary management.” Estado do Sao Paulo goes on to note that Rousseff’s direct influence over monetary policy represents a “dangerous and unmistakable setback.”[4] In order to address this criticism, Tombini felt the need to release a statement declaring his independence from the president.[5]

Rousseff has used her influence over the central bank to keep it behind the curve on inflation. This strategy, which has resulted in a precipitous drop in Brazil’s real interest rates, was intended to generate a relatively higher rate of growth in the short term. While this policy may allow the government to spend more—and increases the likelihood that Rousseff will be reelected next year—the long-term consequence will be inflationary.

To offset the risk of rising prices prior to next fall’s election, and in an attempt to have the best of both worlds, Rousseff has started down the slippery slope of price controls. From her willingness to pressure hotels in Rio de Janeiro to reduce their prices during a G20 meeting, to the recently decreed 30% cut in select electricity prices, she has not shown much restraint. Her targeted strike on electricity prices is particularly disconcerting, as the reductions will deter the electric utilities from making the investment in capacity which Brazil so desperately needs.

Brazilians, having seen this movie before, know how it ends and are reacting. Tomato prices, up some 150% year on year, are a cause célèbre with a cover story in “Veja,” Brazil’s dominant weekly magazine.[6] In the cities of Sao Paulo and Goiana, residents have violently protested the recent increases in public bus fares, as concern over inflation escalates.[7] Most importantly, businesses have slowed down their rate of investment in light of the higher level of uncertainty. As a result, the loose monetary policy might not even have the intended near-term effect of higher economic growth.

We suspect that through a combination of jawboning, rate increases, and price controls, Rousseff will be able to keep inflation under control until next fall. That being said, we recognize that the types of price suppression that Rousseff is engaged in will only result in larger price increases in the future. Consequently, we have become more pessimistic about Brazil’s economic stability and have been sellers of our more fully-valued Brazilian holdings.

Sincerely,

Sean Fieler William W. Strong Daniel Gittes

President Chairman Head of Research

END NOTES

[1] Returns stated for Equinox Partners, L.P. Returns will differ for Equinox Fund International, Ltd.

[2] Analysis uses total sector P&L over total fund P&L multiplied by period performance to derive contribution. Boxed positions are placed in Shorts.

[3] Index: Arca Gold BUGS index (HUI)

[4] O BC domesticado. Estadao do Sao Paulo, May 9, 2012. http://www.estadao.com.br/noticias/impresso,o-bc-domesticado-,870563,0.htm

[5] Brazil central bank: we really are independent! Samantha Pearson, Financial Times, May 10, 2012. http://blogs.ft.com/beyond-brics/2012/05/10/brazil-central-bank-we-are-independent/#axzz2S42h09q3.

[6] Brazil inflation: Surging tomato prices create political headache. Luis Barrucho, BBC Brasil, April 17, 2013. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-22182555

[7] In Brazil, Violence Erupts at Bus-Fare Protest. Loretta Chao, The Wall Street Journal, June 13, 2013. .http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887324188604578543683873774390.html