Kuroto Fund, L.P. - Q1 2011 Letter

Dear Partners and Friends,

PERFORMANCE & PORTFOLIO

Kuroto Fund rose +13.8% in the quarter ended March 31,

2012. After losses in May, the fund was up +4.3% for the year to date through May 31st. This compares to the MSCI Asia Pacific index which was up +0.1% during the same period.

central banking: china versus india

“Chinese premier declares inflation victory,” shouts the Financial Times front page headline of June 24. Quoting from Wen Jiabao’s op-ed inside the edition, the British journal documents the confidence of Chinese authorities that their inflation beast has been slain. Their certainty comes despite the fact that the latest monthly release showed inflation (thought to be significantly understated by the Chinese) continuing to accelerate. In contrast, an editorial in the same FT edition highlights India’s continuing inflation fighting efforts. Despite being remarkably similar to that in China (i.e. both have suffered from serious food price increases for local reasons), Indian inflation is still understood to be a problem, though “price pressures look manageable and, in all probability, temporary.”[1]

Thus, both rapidly growing mega-economies seem to have reason to be optimistic regarding their inflation problem. However, the subtle but important distinction to be gleaned from the newspaper is about the level of conviction evidenced towards each country’s outlook. China can claim ‘victory’ while the FT counsels the Reserve Bank of India to “be cautious.” The different levels of assurance stem from the disparate monetary regimes in both countries—China’s centrally controlled credit apparatus versus India’s market based mechanism. While China’s promise of short-term apparent certainty seems attractive, it also has significant long-term risks. Kuroto’s strong preference is for India’s free market oriented money and banking system, and consequently, India as a location for our partners’ capital.

China’s recent anti-inflation actions appear consistent with orthodox monetary policy. Wen Jiabao’s op-ed cites deposit rate and reserve requirement increases as evidence of China’s resolve. But in point of fact, these standard measures of money tightness seem to be more show than substance: “In China … the Party controls the banks and the banks lend as directed, to state-owned entities.[2]” In other words, in China’s command economy, monetary policy is managed by fiat of the Party—a function of the People’s Republic’s obsession with control. This is accomplished “with a phone call,” to quote CLSA’s bullish China expert, Andy Rothman.

As a result of political interference, China’s credit process is riddled with inefficiencies, anomalies and corruption. Even though these problems are not readily visible to the outside world, anecdotal evidence of significant misallocation of credit, particularly recently at the local and regional level, is ubiquitous. In that same vein, a recent Wall Street Journal opinion piece points out the following:

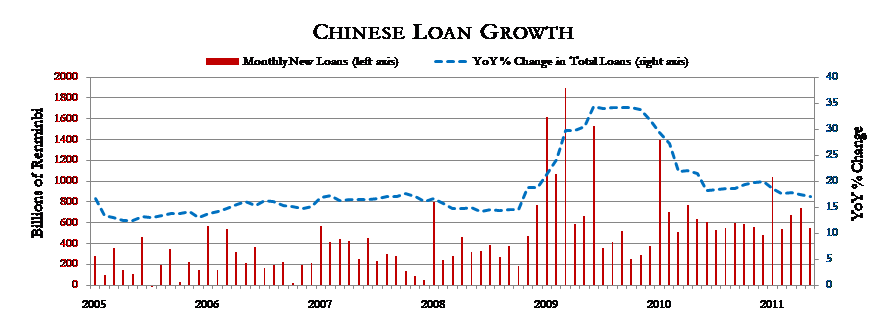

“When the global financial crisis affected China's exports in 2008, Beijing ordered its banks to support a massive credit expansion to create jobs and stimulate growth. The banks eagerly went into action, and in 2009 and 2010 made new loans amounting to a total of 20 trillion yuan ($3.1 trillion). A significant amount of these went to local government borrowers. Estimates of how many would go bad range from 25% to 30%, which suggests a total figure of eight trillion to nine trillion yuan.”

[3]

“The first wave of problem loans originating from the 2009 economic stimulus is about to hit China's banking system. If the reports citing anonymous officials are true, Beijing is considering assuming responsibility for some two trillion to three trillion yuan ($300 billion - $450 billion) of loans that were made to local government borrowing vehicles.

The scale of such a rescue is staggering—at about 7% of gross domestic product it is bigger than the U.S. Troubled Asset Relief Program. It also comes out of the blue; the banks' audited accounts still show that their nonperforming loans have fallen dramatically.”[4]

But don’t expect a US-style credit crunch in China or even an acknowledgment of the problem. A closed financial system coupled with phony accounting and another round of large government bank bailouts will paper over the difficulties—perpetuating the illusion of financial tranquility.

India’s messy, but essentially orthodox, policy environment is more to our liking because it is closer to a market model. For example, India has followed a far more conventional monetary policy along with strict limits on banking practices. Chris Wood, CLSA’s Asia investment strategist, expresses our sentiments well: “[T]he Reserve Bank of India (RBI) remains a wonderful example of what a central bank should be. That is an institution whose primary concern is ensuring the safety and soundness of the local banking system.”[5]

While Kuroto has raised tactical concerns that the Indian monetary authority had fallen “behind the curve” in the last year in their fight against inflation (see the Kuroto Q1 2010 letter), we concur with Mr. Wood’s endorsement of the RBI’s disciplined stance against aggressive lending practices that lead to speculative bubbles. For example, Indian bank regulations, in contrast to those in the US, discourage securitization of loans. Since 2006, Indian banks have not been allowed to realize gains on securitized loans at the time of their sale. Thus discouraged, there were few excesses attributable to securitization and therefore few banking problems in 2008.

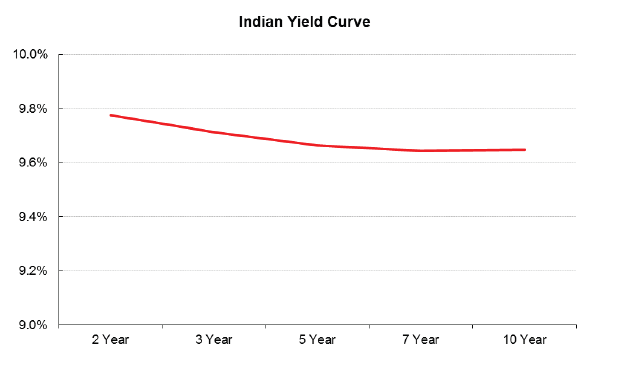

The RBI seemed to be in denial last year about its growing inflation problem. Attributing price increases (India still uses a wholesale price scale which overweights food) to food inflation caused by a one-off bad monsoon, they delayed painful tightening moves. However, in 2011, the RBI has aggressively tightened money market conditions to the point of an inverted yield curve (see graph below) and the economy has begun to respond. For instance, after recording a growth rate of 29% in fiscal year 2010-2011, the passenger car industry growth has slowed to a 20 month low of 7% in May. On June 24, Maruti Suzuki, India’s largest car maker lowered its sales growth target from 13% to 8% for fiscal year 2011-2012, with a senior executive citing rising interest rates and the increase in the price of gas as reasons for consumers deferring purchases, particularly at the entry level.[6]

While the necessary monetary tightening has been modestly painful for our portfolio, we believe that India has corrected its tardiness and has joined the inflation fight in earnest. It appears that after a modicum of additional tightening, India will be back on the road to sustainable, rapid growth—even with the uncertainties inherent in market mechanisms for the transmission of conventional monetary policy.

To conclude, we are often asked why Kuroto chooses to invest heavily in one of the two Asian BRIC countries, India, while our exposure to the other is virtually nil. The answer has much to do with our stock selection process: focused on fundamentals of individual businesses and managements. But Kuroto also considers the investment environment of countries, including that produced by the monetary authorities in each country. By this measure, Kuroto’s lopsided preference for India is well illustrated by the very different central banks of India and China.

Sincerely,

Sean Fieler

William W. Strong

ENDNOTES

[1] Financial Times, “India should keep calm on inflation”, June 24, 2011.

[2] Carl Walter and Fraser J.T. Howie, Red Capitalism: The Fragile Financial Foundations of China’s Extraordinary Rise, 2011, page 206.

[3] Carl Walter and Fraser J.T. Howie, Wall Street Journal, “Beijing’s Financial Day of Reckoning is Near”, June 21, 2011.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Chris Wood, Greed and Fear, June 2, 2011, page 3.

[6] Business Standard, New Delhi, “Maruti lowers sales growth forecast”, June 24, 2011.