Kuroto Fund, L.P. - Q1 2010 Letter

Dear Partners and Friends,

PERFORMANCE & PORTFOLIO

Kuroto Fund, L.P. appreciated 13.7% in the quarter ended March 31,

2010. As of May 31, 2010, our fund was up 13.9% for the year-to-date.

Indian Inflation

It’s hot and dry in India this time of year—very hot. As we write, it is 108 degrees with “blowing widespread dust” in New Delhi. So, it is not hard to understand the anticipation with which Indians await the annual monsoon season that should begin soon. In a country where over half the population is still employed in agriculture, this seasonal weather pattern, providing 75% of India’s annual rainfall, has a large impact on the economy.

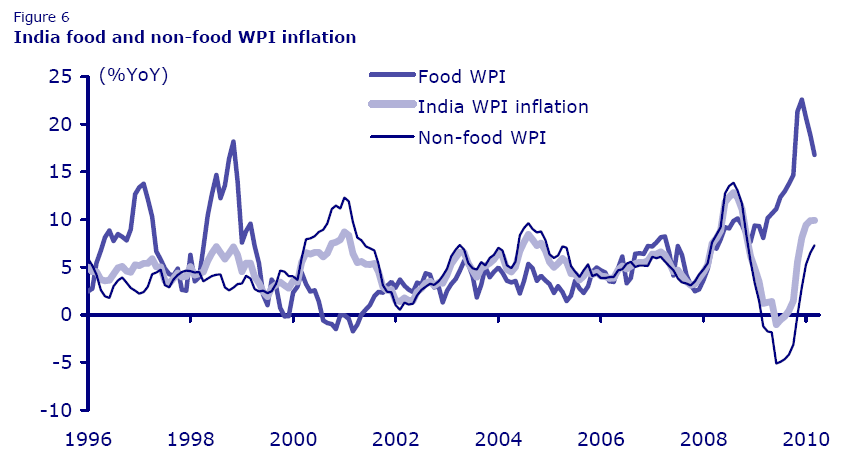

Last year’s Indian monsoon was disappointing—the weakest in 37 years. In the northwest part of the country, rainfall was off 39% and agricultural production suffered significantly. Rice production in all of India, for example, declined by an estimated 18%. As a result of the subnormal monsoon season, food prices rocketed higher, touching off a 20% year-over-year increase by December 2009 and sharply accelerating the heavily food-weighted inflation indices (see graph below)

Six months ago, UBS framed the issue of Indian inflation well:

The common received wisdom in the market today is that India is one of the very few EM countries facing an immediate and urgent inflation problem. At a time when consumer price inflation rates in the emerging world have been falling sharply for the past 12 months and are only now beginning to trough, India is the only major economy where official headline CPI inflation has not only been accelerating steadily through the year but is also much higher than in the previous boom period. From an average rate of 6.4% in 2007 and 8.3% in 2008, official consumer inflation for industrial workers reached 12% yoy over the past three months (and the alternative measures for agricultural and rural laborers are higher still).

These figures put both short-term interest rates and long-term bond yields in sharply negative territory, and in turn suggest that the RBI is far more ‘behind the curve’ than any of its global counterparts, heightening apparent risk of aggressive policy hikes just around the corner—and perhaps a sudden and painful shake out in the bond market.[1]

The UBS economic team goes on to express their opinion that these inflation figures appeared at the time to be significantly overstated. The divergence between India’s Consumer Price Index (CPI) and its Personal Consumption Expenditures Deflator Index signals a flaw in India’s CPI measure. In the Indian CPI, “service prices are both mismeasured and under represented in the basket, and thus the headline index is overly sensitive to recent food price spikes.” The misalignment of India’s CPI index would appear to be confirmed by their Wholesale Price Index (WPI) which fell dramatically in 2009.

However, that was then and this is now. Today, even Indian wholesale prices are rising at an alarming rate—the WPI rose 10.2% year-over-year in May, above expectations and higher than the 9.6% rate recorded in April. In addition, March was revised upward from 9.9% to 11%. These numbers compare to a 1.4% rate a year ago (see graph on page 1). More worrisomely, the composition of price acceleration is changing: “there is a clear shift in price pressure from agro to industrial commodities in the last 5 or 6 months.”[2] For example, ‘basic metals, alloys and products’ showed a year-over-year increase of 12.1% versus a year-over-year decline of over 13% in May of 2009. Consumer price inflation has remained quite high but is starting to moderate slightly because food prices are easing a little.

In the short run, there is reason for some optimism. Global commodity prices have weakened substantially in recent months (copper has dropped from $3.80 to $2.90/lb) and it appears that some of the local strength in industrial prices is coming from the underreporting of previous increases. The Indian brokerage firm Edelweiss believes that inflation has peaked and will stabilize at around 5% by the end of the calendar year. Goldman Sachs is less optimistic and forecasts a rate of 7.5%.

Despite the ambiguities and uncertainties of their inflation measurements, we see serious structural problems in containing Indian inflation in the longer term. The numerous and well documented deficiencies in the country’s infrastructure are a constraint on the country’s rapid economic expansion—turning increasing demand into higher prices rather than more output. For example, returning to food inflation, there is evidence that the spurt in food prices is not just a result of a bad monsoon season. Rather, it seems to have a secular upward bias. Illustrating this trend is the fact that food prices started accelerating before the jump caused by poor rainfall (see graph on page 1). Moreover, an even worse monsoon season in 2002 did not result in anything like the food price increase seen last year. Growing per capita income leads to more food consumption. However, the productivity of the farm sector has lagged behind income growth, and as a result, supplies of food stuffs have diminished.

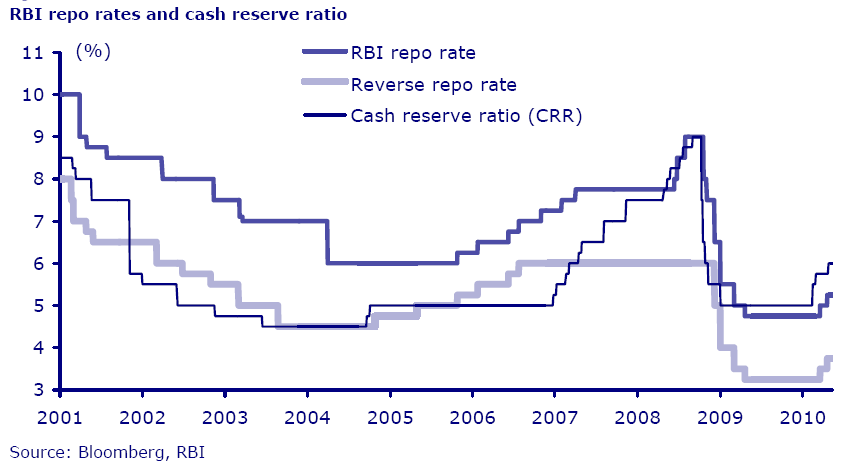

Given the large gap between current inflation and interest rates, the Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI) view of these inflation statistics is of particular relevance. So far the monetary authorities have raised interest rates slightly and tightened reserve requirements (graph below).

Credit Suisse stresses the predicament the RBI finds itself in:

The RBI has been highlighting the dilemma it faced on whether or not to tighten monetary policy given that recent inflation pressures were mostly food driven. The central bank has generally maintained that it is difficult to ignore food price inflation pressures beyond a point as these impact people’s ‘perception’ of inflation and that in turn influences inflation ‘expectations’. [3]

In Kuroto’s view, monetary policy tightening in India probably has a way to go. We expect the RBI to raise rates in the coming months, until local rates are clearly back in “real” territory. Though usually not a bullish context for stock prices, tighter money is a necessity for economic health and can be viewed as the price investors must pay for higher nominal earnings growth. Our Indian businesses, still attractively valued, should continue to expand at impressive rates.

Finally, the most important implication of accelerating inflation in India, and indeed across Asia, may well be the end of the long-running and unhealthy policy of tying undervalued Asian exchange rates to the US dollar. Because Asia is not burdened with the massive debt deflation problems of the US, Europe, and Japan, these developed region’s extremely low interest rates are now completely inappropriate for emerging Asia. But raising their interest rates back to normal or even “tight” levels in these Asian countries would undoubtedly produce strong upward pressure on their currencies—a heretofore unacceptable restraint on their exports. However, India seems to have ceased foreign exchange targeting for the rupee some time ago and China has just announced that it will resume the policy of allowing the renminbi to appreciate. Other Asian currencies have also appreciated. Both countries (and Brazil, another BRIC member) have begun monetary tightening with the concomitant expected modest currency appreciation. It will be interesting to see how much currency appreciation policy makers will tolerate and whether they will then resort to capital controls. As Kuroto’s investments in Asian stocks are unhedged for currency moves, we welcome an era when Asian money begins to normalize. (For the year-to-date we calculate foreign exchange appreciation has added 1% to Kuroto’s performance this year).

By the way, our two analysts/meteorologists currently in India report it rained every day last week in Mumbai. Expectations are for a normal monsoon season this year in India.

Sincerely,

Sean Fieler

William W. Strong

ENDNOTES

[1] UBS report, “Emerging Market Focus: India’s Hard Choices (transcript)”, January 4, 2010.

[2] Edelweiss report, Monthly Indicator, “Inflation Crosses the psychological mark of 10%”, June 14, 2010.

[3] Credit Suisse report, “India: Food Price Inflation—not just a one off”, February 9, 2010.