Equinox Partners, L.P. - Q4 2011 Letter

Dear Partners and Friends,

PERFORMANCE & PORTFOLIO

Equinox Partners fell -1.3% in the quarter ended December 31, 2011. In 2011, Equinox Partners declined -28.0%. In January, the fund was up +11.8%.

Equinox’s decline in 2011 surpassed that of the Credit Crisis in 2008, previously our largest annual drawdown. Whereas profits on our short positions partially offset some of the losses on our long positions in 2008, last year, Equinox lost money on all four of our major themes (i.e., long superior operating businesses in emerging markets, long energy and gold mining companies, and short developed world sovereign debt). Because our longs declined much less in 2011 than 2008, they are nowhere near as cheap as they were at the lows of 2008. Consequently, we do not expect a repeat of the dramatic rebound that we experienced in 2009.

Correlation

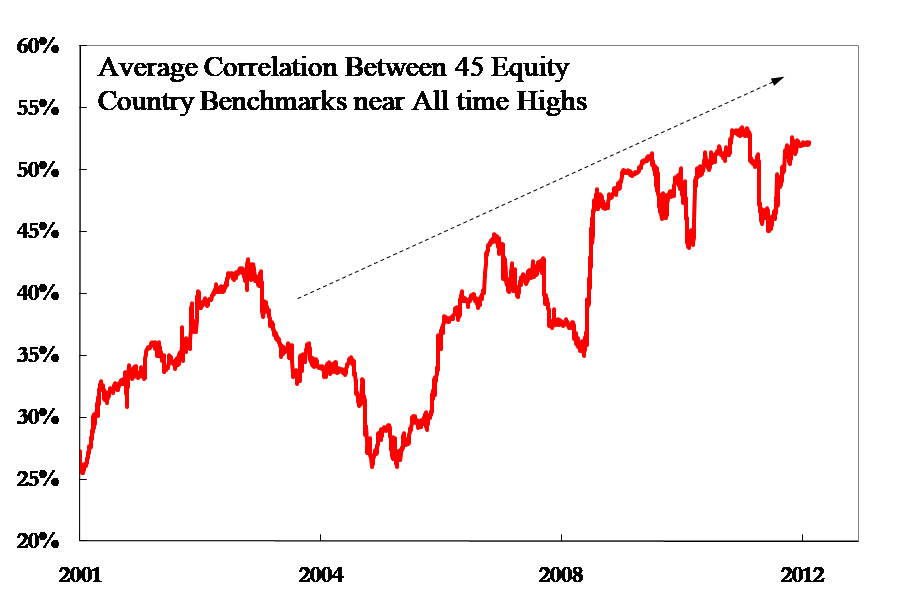

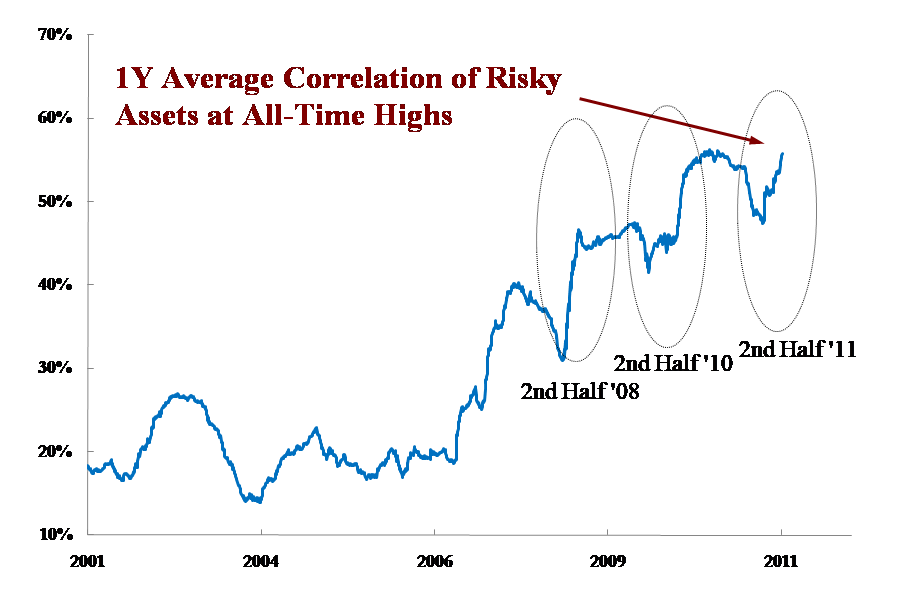

While the financial results of domestically-oriented Brazilian and Indian companies have little to do with one another, in 2011 the stock market traded the two as though they were rough equivalents. As a result of this increased correlation, our globally diversified portfolio of fifty companies across 14 countries provided little daily diversification.

To many, rising price correlations across countries appear to be the inevitable consequence of an increasingly interconnected world. But, this simplistic view over weights the importance of increased information flows and mischaracterizes the significance of growing global trade. With respect to information flows, for example, Greece’s debt crisis has captured the entire world’s attention in a way that is completely out of proportion with its actual economic significance. With respect to global trade, its persistent growth belies the emerging markets’ deliberate use of trade to insulate their economies from, rather than integrate their economies into, the global economy.

When Equinox Partners opened its doors seventeen years ago, much of the Emerging World was dependent upon short-term dollar borrowings to finance their large current account and fiscal deficits, and predictably, whenever the Developed World so much as sneezed, the Emerging World got pneumonia. The method of transmission was perfectly clear: as liquidity dried up in the Developed World, currencies of countries that needed to rollover foreign debt declined, thereby making the debt rollover more difficult, which in turn aggravated the currency declines. Today, the underlying fundamentals are almost exactly reversed, despite increases in global trade. Having diligently exported their way to massive trade surpluses over the past decade, the Emerging World now holds trillions of dollars in foreign exchange reserves. These reserves have reduced the Emerging World’s dependence on Developed World capital markets for debt financing and have consequently put the Emerging World in an excellent position to be protected against global economic shocks.

Furthermore, that the correlation of almost all financial assets including commodities (see graph above) is increasing both within and across countries, suggests that it is the unit of account, not the underlying assets, that is changing in value. We are not claiming that the US dollar’s purchasing power is fluctuating widely, but that periodic deflationary and inflationary scares are just another way of describing wide fluctuations in the US dollar’s perceived future purchasing power. This looming threat of monetary instability—not growing global interconnectedness—best explains the recent remarkable increase in the correlation of assets within and across national borders. As the unit of account appreciates and depreciates, it is everything else that appears to go up and down.

Staying the Course

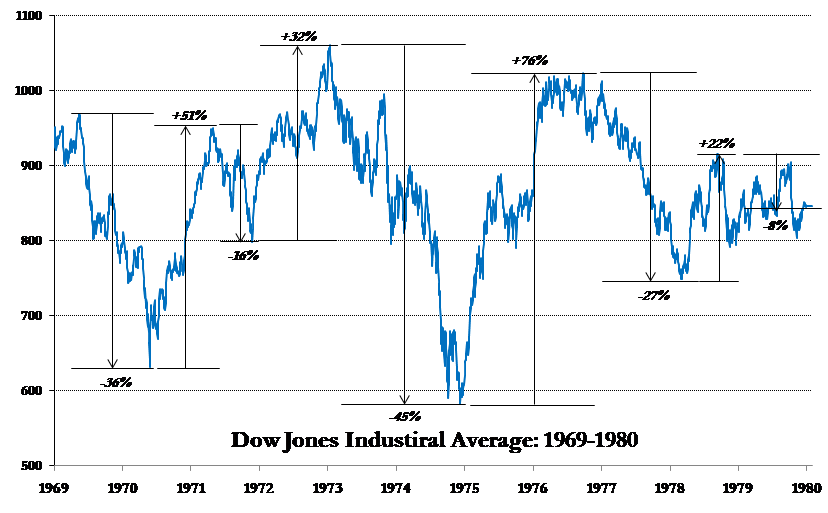

While more than thirty years have passed since Americans have had to contend with actual dollar instability, it is for good reasons that the experience of investing against a backdrop of dollar volatility is still seared into the memory of anyone who lived through the 1970s. For most equity investors, the experience was trying. Not only did the dollar lose more than half of its value over the course of the decade, but the dollar volatility and corresponding policy responses induced a series of massive rallies and breathtaking declines in stock prices. The graph below shows the price movement of the Dow Jones Industrial Average in the 1970s and graphically illustrates this rollercoaster ride of a decade.

Looking at the above chart, it is easy to conclude that one must actively trade in times of monetary instability. This is exactly wrong. Not only are the rallies and declines unpredictable, but a focus on trading can obscure the long-term opportunity to buy great businesses at exceptional prices. Rather than attempting to time the market, a few particularly thoughtful investors, such as Warren Buffett and Bill Ruane, recognized that the indiscriminate buying and selling by other market participants created exceptional opportunities for patient, disciplined investors. As a reward for their disciplined approach, they both compounded their capital at admirable rates over the course of the decade.

The sine qua non of a long-term value approach in a turbulent market is the ability to identify businesses that will grow profitably despite a challenging economic backdrop. On this point, based on our estimates, we are pleased to report that the earnings of our portfolio companies grew at +16% last year on a look-through basis.

As we remain disciplined value investors in what promises to be a volatile period, we hope that our partners will realize that the good years aren’t as good as they seem, the bad years aren’t as bad as they seem, and that a volatile and indiscriminate market will inevitably provide us with opportunities to buy exceptional businesses at attractive valuations.

Privacy Policy

The world over, there is a growing sense that market forces need to be more closely managed by a political or expert authority. One manifestation of this growing sense is increased taxation and control over cross-border capital flows. As global investors, it should surprise no one that we have started receiving inquiries from governments about the nature of these capital movements. Last year, for example, we received requests from South Korea and Egypt asking us to verify that we have no Korean or Egyptian investors by disclosing the names and nationalities of our clients. We were able to comply with the request in these two cases by only disclosing the domicile and not the names of our investors. That said, we suspect that Korea and Egypt are merely ahead of the pack, and that going forward we will periodically be required, or incented, to disclose more information about our clients in order to invest in certain markets. You can be assured that we will always weigh these decisions carefully, disclosing the minimum amount of information necessary to achieve the preferred tax treatment. The larger point to grasp, however, is that we, like our competitors, will likely face increased regulatory pressure to disclose more client information to governments in the future.

Escape from New York

It is no secret that New York City is one of the most expensive jurisdictions to do business. Mayor Bloomberg has even referred to his city as a “luxury product.” While we are distressed by the City’s pricing power, we are even more distressed by the condition of the State’s finances. New York State’s pension liability is $120 billion underfunded[1] and, according to the New York State constitution, the benefits cannot be reduced in any way. This puts New York State in a difficult position, and makes tax increases extremely likely, if not quite inevitable in this already highly taxed jurisdiction.

Despite these likely tax increases, for our business purposes, New York City remains attractive—the benefits still outweigh the costs for this “luxury product.” But for the principals of the business, living in the City makes less and less sense. For Bill Strong in particular, who pays more in city and state taxes than he does in federal taxes, is not focused on the daily operations of the business, and can participate in the investment decisions remotely, the incentive to relocate to a lower cost jurisdiction is too attractive to ignore.

Accordingly, Bill has purchased a home in Florida, a state, not incidentally, with no income tax. He remains in good health and is not retiring (Bill doesn’t play golf). We are also restructuring his management company interest so that Bill can participate in the business through a Florida-based entity while retaining his significant financial stake in the business. He will maintain an office in Miami in order to keep regular hours and to easily communicate with our research team and investors. Bill will also travel back and forth to New York and will continue to take research trips with our analysts. If you’re wintering in the Miami area, we encourage you to please stop by and visit him.

Sincerely,

Sean Fieler

Daniel Gittes

William W. Strong

END NOTES

[1] Empire Center for New York State Policy, EJ McMahon and Josh Barro, New York’s Exploding Pension Costs, December 2010. (Analysis includes both the New York Teachers’ Retirement System and the New York State and Local Retirement System using private-sector accounting standards to calculate funding shortfalls. Does not included $76 billion New York City pension unfunded liabilities.)