Kuroto Fund, L.P. - Q4 2011 Letter

Dear Partners and Friends,

PERFORMANCE & PORTFOLIO

Kuroto Fund, L.P., declined -3.0% in the quarter ended December 31,

2011. The fund was down -14.2% in 2011. This compares to the MSCI Asia Pacific index which declined -14.9% for the year. In January, the fund appreciated +6.4%.

Return on Equity: Lost in Japan

At inception, Kuroto adopted Charlie Munger’s quote to demonstrate our intention to limit our value investments to “great” businesses. By “great” we meant—and we are confident Munger meant the same—companies with strong competitive positions that can generate superior profitability, or return on shareholders’ equity (ROE), over long periods of time. Also, like Munger, we recognize the importance of “great” managements. Harvard Business School’s competitive strategy guru, Professor Michael Porter, would seem to agree with Charlie Munger’s view on profitability. He asserts that profitability is the “measure of the economic value [add] of a company.” Neither business sage would get a vociferous argument from Kuroto Fund.

In 2011, the superior returns on shareholders’ equity of our undervalued businesses, even in tandem with the rapid growth of emerging economies which are barely exposed to the European financial mess, did not work to create a positive return in Kuroto’s stock portfolio. This is, in itself, not particularly noteworthy given the limited time horizon of a single year. But, because some might mistakenly extrapolate last year’s Asian market disappointment into the future, we thought it might be useful to remind partners why we remain sanguine about our holdings, regardless of the fate of the over-indebted Developed World.

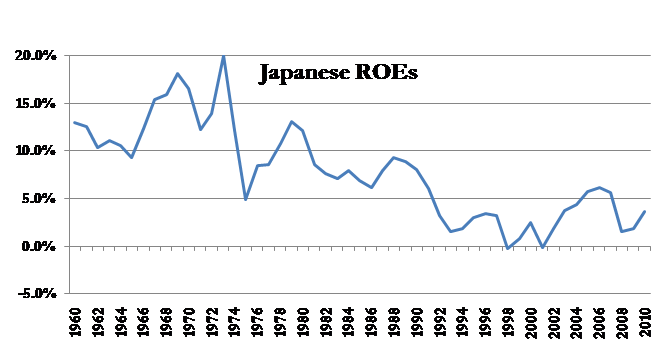

Our central point about Asian investing in general can be clearly made by examining the glaring Asian exception to the rule—namely Japan and the value destruction that resulted from low Japanese ROEs over the past three decades. Data that has recently come to our attention regarding the returns earned by Japanese businesses show consistently poor ROEs in the aggregate. The graph below illustrates that Japanese companies earned, on average, an 8% return on equity during the period starting in 1960 until now. This is less than half of what Asian companies outside of Japan have generated for their owners.

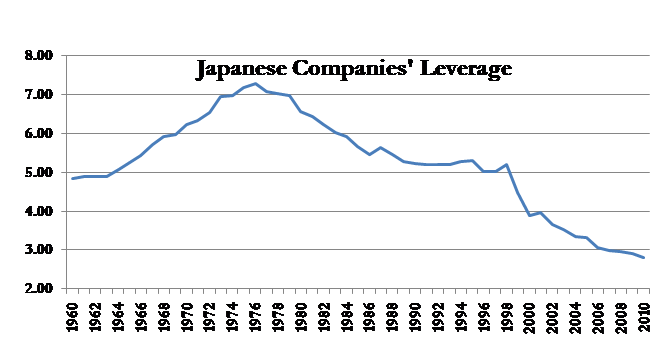

But digging deeper into the Japanese returns reveals even more substandard results. Because of their extremely low profit margins, Japanese businesses have only earned about 1% on their total assets since 1960 (Asia ex-Japan companies, in contrast, earned return on assets (ROA) of about 8% in the last decade). As the graph below clearly shows, these low ROAs have translated into declining ROEs over the last two “lost decades” in Japan as Japanese businesses have reduced leverage. Discussing his research on Japanese businesses more than a decade ago, Michael Porter states, “The persistent inability to produce a good return on investment is the most fundamental sign of the flaws in the Japanese system.”[1] This, in a nutshell, is why Kuroto has had a very limited exposure to Japanese equities.

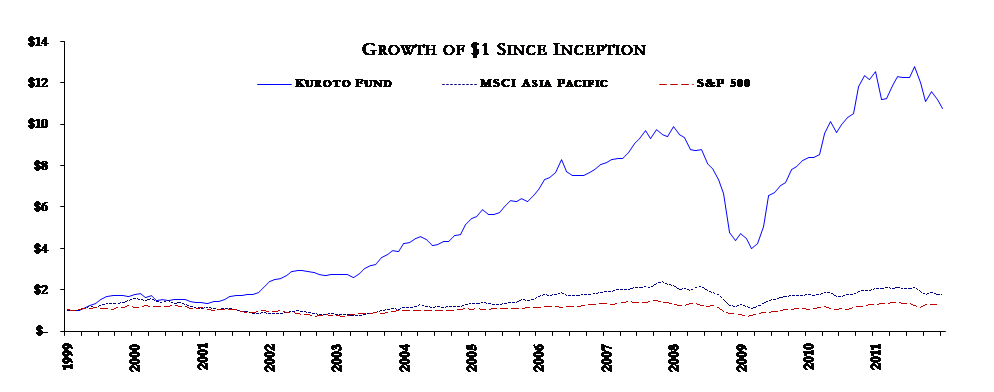

For Japanese equity investors, the result of inadequate return on capital has been catastrophic—near 0% returns over the last thirty years in Japanese stocks. In Yen terms, despite the 1980s massive speculative blow off, the Nikkei 225 is now where it was in 1982! Compare this to the results generated by the selection of high-return Asian companies owned by Kuroto Fund since 1999:

We estimate that the current mix of profitable, well-capitalized, local Asian businesses in our portfolio produced a +17% ROE in 2011 and, while there can be no assurance, we estimate that they will generate an +18% ROE in 2012. While financial and economic uncertainty characterizes the outlook for 2012, we believe our businesses will once again add substantially to their intrinsic value. When this will be reflected in their stock prices, we don’t know—but the compression of valuations in 2011 has made our portfolio more attractive.

Privacy Policy

The world over, there is a growing sense that market forces need to be more closely managed by a political or expert authority. One manifestation of this growing sense is increased taxation and control over cross-border capital flows. As global investors, it should surprise no one that we have started receiving inquiries from governments about the nature of these capital movements. Last year, for example, we received a request from South Korea asking us to verify that we have no Korean investors by disclosing the names and nationalities of our clients. We were able to comply with the request by only disclosing the domicile and not the names of our investors. That said, we suspect that Korea is merely ahead of the pack, and that going forward we will periodically be required, or incented, to disclose more information about our clients in order to invest in certain markets. You can be assured that we will always weigh these decisions carefully, disclosing the minimum amount of information necessary to achieve the preferred tax treatment. The larger point to grasp, however, is that we, like our competitors, will likely face increased regulatory pressure to disclose more client information to governments in the future.

Escape from New York

It is no secret that New York City is one of the most expensive jurisdictions to do business. Mayor Bloomberg has even referred to his city as a “luxury product.” While we are distressed by the City’s pricing power, we are even more distressed by the condition of the State’s finances. New York State’s pension liability is $120 billion underfunded[2] and, according to the New York State constitution, the benefits cannot be reduced in any way. This puts New York State in a difficult position, and makes tax increases extremely likely, if not quite inevitable in this already highly taxed jurisdiction.

Despite these likely tax increases, for our business purposes, New York City remains attractive—the benefits still outweigh the costs for this “luxury product.” But for the principals of the business, living in the City makes less and less sense. For Bill Strong in particular, who pays more in city and state taxes than he does in federal taxes, is not focused on the daily operations of the business, and can participate in the investment decisions remotely, the incentive to relocate to a lower cost jurisdiction is too attractive to ignore.

Accordingly, Bill has purchased a home in Florida, a state, not incidentally, with no income tax. He remains in good health and is not retiring (Bill doesn’t play golf). We are also restructuring his management company interest so that Bill can participate in the business through a Florida-based entity while retaining his significant financial stake in the business. He will maintain an office in Miami in order to keep regular hours and to easily communicate with our research team and investors. Bill will also travel back and forth to New York and will continue to take research trips with our analysts. If you’re wintering in the Miami area, we encourage you to please stop by and visit him.

Sincerely,

Andrew Ewert

Sean Fieler

Daniel Gittes

William W. Strong

ENDNOTES

[1] Michael E. Porter, Can Japan Compete?, 2000, p.77.

[2] Empire Center for New York State Policy, EJ McMahon and Josh Barro, New York’s Exploding Pension Costs, December 2010. (Analysis includes both the New York Teachers’ Retirement System and the New York State and Local Retirement System using private-sector accounting standards to calculate funding shortfalls. Does not included $76 billion New York City pension unfunded liabilities.)