Equinox Partners, L.P. - Q3 2015 Letter

Dear Partners and Friends,

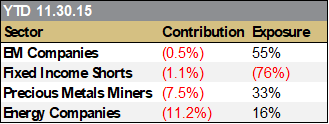

PERFORMANCE & PORTFOLIO

Equinox Partners fell -25% in the third quarter. After a modest rebound in October and a further drop in November, the fund had declined -23% for the year to date through November 30.[1]

With Equinox Partners down a cumulative 50% from its year end 2010 high water mark, we thought it time to review “what we got wrong” as well as, more modestly, “what we got right” over the period. While we made some glaring company-specific errors—Health Care Locums and APR Energy come to mind—the vast majority of our losses have come from our poor assessment of first world central banks and commodity prices.

For years, we have expected first world central banks to lose their credibility as they proved unable to reverse the massive monetary experiment that has characterized their polices since the global financial crisis of 2008. This has not happened. We compounded this error by investing in energy companies with the expectation that oil prices would stay above $80 and natural gas prices would stay above $3. Finally, even though our globally diversified operating businesses have appreciated over the past five years, the aforementioned misjudgments corresponded with a substantial headwind in emerging markets where most of these businesses operate.

While our mistaken assessment of first world central banks and the energy markets have cost us dearly, we are not changing course. To loosely quote Chris Cole of Artemis, central bankers are “trapped” in a “prison of their own design,” unable to “remove extraordinary monetary accommodation without risking a complete collapse of the system…”[2] Accordingly, we see the Fed’s expected December rate hike as the first step towards the end of the normalization narrative rather than a confirmation of an inevitable return to meaningful positive real rates. As we wrote a year ago in our third quarter 2014 letter:

“…despite the Fed’s protestations to the contrary—a return to meaningful positive interest rates, i.e., historically normal monetary policy, is extraordinarily unlikely. Our basis for this view rests on our confidence that meaningful real rates would put too great a burden on the still over-indebted Developed World economies. Central banks will, therefore, not normalize rates so long as the Developed World’s mountain of debt remains in place.”

Persistent Central Bank Credibility - Our Largest mistake

By keeping rates extremely low, expanding their balance sheets by trillions of dollars, and encouraging growth in global debt, first world central banks have embraced almost the exact set of policies we predicted they would. Perversely, the monetary policy that we thought would produce inflation may have temporarily reinforced deflationary expectations by encouraging an enormous respect for central banks as price fixers. Less controversially and more certainly, a combination of broad-based commodity deflation and a weak global economy has clearly helped anchor inflationary expectations and propped up central bank credibility at a time of truly unprecedented monetary policy.

The persistent credibility of first world central banks has been a disaster for our sovereign bond shorts. Ever since a clear moment of weakness in 2011, first world central banks have successfully used their expert authority and unlimited printing presses to manipulate down government bond yields. Who would have imagined that Mario Draghi could drive down 10-year bond yields in Italy and Spain from roughly 7.5% in the fourth quarter of 2011 to an average of 1.5% today? Similarly, the Bank of Japan has driven rates down across the Japanese yield curve—the yield on the 20-year JGB has declined from a 2011 high of 2.1% to 1% today. Even the Federal Reserve has managed to oversee a decline in interest rates on the 10-year bond, from 3.7% to 2.2%.

Despite their success to date, we still do not believe that central banks can monetize such large amounts of government debt without significant adverse consequences. One adverse consequence already apparent is the extreme short-term focus of the first world central banks and the excessive importance placed on small changes in monetary policy. The Fed’s prospective 25bps rate increase is a case in point. The notion that such a small increase could jeopardize an economy reflects a scary reality that should not inspire confidence. Rather, the incessant handwringing about a quarter point should instead inspire fear that there is so little margin for error.

John Taylor, Stanford economist and plausible successor to Janet Yellen under a Republican administration, recently expressed his exasperation with a data-dependent Fed that struggles to provide an organizing framework for its actions and treats each incremental decision with enormous importance: “No one knows what you’re doing,” Taylor told William Dudley, President of the New York Fed.[3] Taylor is not alone. St. Louis Fed president Jim Bullard and others inside the Fed have openly admitted that they struggle to explain the current effect of monetary policy on the real economy. Amazingly, this inability to provide a credible framework has not yet cost the Fed its credibility.

the collapse of energy prices - our second big mistake

During 2014 and 2015, we made several trips to Calgary and Texas to meet with energy companies. While the resulting investments have made the E&P sector our single largest loser so far this year, we remain impressed with the prospects of the companies in which we’ve invested. As we have noted in past letters, our companies have incredibly long-lived assets and, at slightly higher energy prices, trade at very attractive multiples to cash flows that can grow for more than a decade.

The poor performance of our E&P investments is largely, but not exclusively, a result of our failure to accurately assess the short-term supply and demand of both oil and gas. Most notably, oil production remains two million barrels per day in oversupply, a majority of which can be attributed to increased output from OPEC. As has been widely reported in the press, rather than serve as swing producer, Saudi Arabia has actually increased production as prices have declined. Given petroleum’s very low price elasticity and the absence of a swing producer, we are now in an era of exaggerated price swings. As painful as the downside has been, it is important to note that this dynamic cuts both ways. The potential upside is equally large. With this in mind, the ongoing declines in production should take on new significance. While it could be another year before those trends overwhelm the current market oversupply, the end result of higher prices appears both inevitable and substantial.

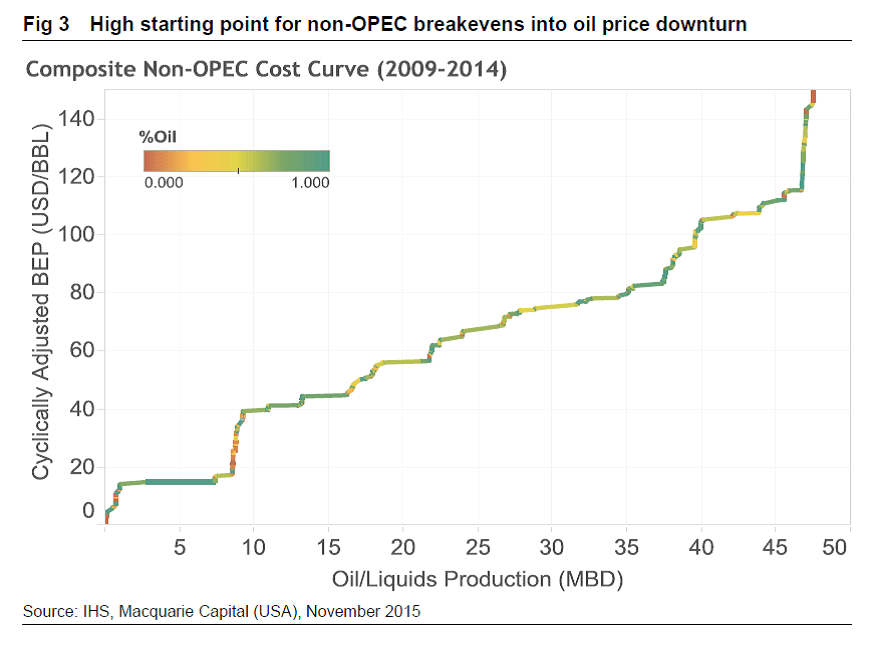

To calculate the unsustainability of today’s prices, marginal replacement cost analysis provides the best framework in our opinion. As the “cost curve” of non-OPEC energy companies makes clear (see below), equilibrium pricing for much of the world’s petroleum production is considerably higher than today’s sub-$40 spot prices. Even accounting for the rapid cost declines experienced by the 5% of global oil output that comes from shale, the average non-OPEC producer is still nowhere close to sustaining production at current energy prices. The specific E&P companies we own, however, are well into the left tail of the graph below and capable, if not comfortable, sustaining production as current prices.

Approaching the same analytical problem from another angle, the massive cut backs in capital expenditure in the E&P sector confirm the unsustainability of global production at current energy prices. In fact, given the huge declines in drilling in North America and cutbacks in capital expenditure globally, we think that production declines could accelerate quickly. And, given project lead times, it will take time to add capacity even at higher prices.

looking forward: "lift off"

For many years Equinox has publically, frequently, and uncompromisingly expressed doubt about central bankers’ resolve to return monetary policy to “normal.” Consider that despite six years of economic expansion real policy rates in the U.S. are still negative. This was in part possible because over the past four years, commodity prices have kept headline inflation down, thereby giving space to an otherwise constrained Fed. The inverse, we note, should also be true. If history is a good guide, a typical rebound in commodity prices would likewise meaningfully boost U.S. inflation. This outcome, we believe, would cost the Fed its credibility if it did nothing or send the economy into recession if the Fed reacted appropriately. While definitely contrarian, it is worthwhile to consider the possibility that commodity prices, now below replacement costs, will rebound and put first world central banks in an impossible situation.

More generally, the Fed is anything but confident in their path to normalization. Yellen is regularly dampening expectations about the rapidity of rate increases. In a recent letter to Ralph Nader she wrote the following: “Most of us expect the pace of that normalization to be gradual.” She then specifically raised the possibility that aggressive rate increases “would undercut the economic expansion, necessitating a lasting return to low interest rates.”

To our mind, more important than the precise timing of rate increases is the Fed’s ultimate policy objective. That an uneven economic recovery and ever increasing debt load make meaningfully positive real rates (i.e., normalization) a near impossibility is the critical point. Yellen herself implicitly admits this truth by never specifying what normalization means. Other Fed officials have chosen to redefine “normal,” thereby making a return to normalcy more achievable and lending credence to our view that the old normal is not possible. In a paper published just this October, John Williams, Yellen’s successor at the San Francisco Fed, advocates a redefinition of normal as zero real rates.[4]

Rather than redefine normal as zero real rates, we think it is more intellectually honest to admit that the Fed has gone down a path of no return. To quote Chris Wood, “central banks, most importantly the Fed, will not be able to exit from unconventional monetary policy in a benign manner… Such policies will ultimately discredit central banks pursuing unconventional monetary policy.” This outcome, of course, is not something the Fed will admit, but, rather something the market will have to prove. With the Fed finally moving off the zero bound, their largest test yet is fast approaching.

The unsustainability of the current monetary policy and commodity prices bodes well for Equinox’s future. As today’s toxic mix of commodity deflation and unchallenged central bank credibility proves to be temporary, we expect our portfolio to turn around sharply. Specifically, we expect strong emerging markets, higher gold and silver prices, higher first world bond yields, and higher energy prices. In this changing environment, other opportunities may present themselves. For instance, on a short-term basis, U.S. companies will likely face increasing headwinds, making U.S. companies more interesting from a short perspective. On a long-term basis, these headwinds may make U.S. companies more attractive investments as multiples decline.

Sincerely,

Andrew Ewert

Sean Fieler

Daniel Gittes

William W. Strong

END NOTES

[1] Sector exposures calculated as a percentage of 11.30.15 post-redemption AUM. Therefore, exposure will vary from forthcoming monthly summary which uses 11.30.15 pre-redemption AUM. Performance contribution as stated uses fund’s dollar-weighted gross internal rate-of-return calculations derived from average capital and sector P&L. Sector performance figures derived using monthly performance contribution calculations in US dollars, gross of fees and fund expenses. Interest rate swaps notional value included in Fixed Income exposure and contribution. P&L on cash and U.S. equity options excluded from the table as are market value exposures for derivatives; their combined contribution is -1.5% of average capital.

[2] Chris Cole, Artemis Capital, October 2015

[3] Jon Hilsenrath, The Wall Street Journal, The Fed Strives for a Clear Signal on Interest Rates, October 26, 2015.

[4] Thomas Laubach and John Williams, Measuring the Natural Rate of Interest Redux, October 31, 2015.