Equinox Partners, L.P. - Q3 2009 Letter

Dear Partners and Friends,

PERFORMANCE & PORTFOLIO

Equinox Partners appreciated 27.9% in the third quarter and was up 108.2% for the nine month period ended September 30th.

Brazil's Entrepreneurs

Brazil is an extremely difficult place to run a business but a great place to invest in one. Ranked 129 out of 183 countries in the World Bank’s 2010 Doing Business Report, Brazil is undoubtedly a challenging country in which to operate. The World Bank scored countries on ten criteria: starting a business, dealing with construction permits, employing workers, registering property, getting credit, protecting investors, paying taxes, trading across borders, enforcing contracts, and closing a business. Brazil’s overall score places it behind the likes of Nigeria and Bangladesh, and on particular issues, such as the ease of paying taxes, Brazil ranks behind Haiti and Bolivia. Not the public policy prescription we would recommend, but this hostile environment has produced a particularly robust group of business models and entrepreneurs.

While the Brazilian government often made operating a business next to impossible, it always stopped short of making the operation of a business actually impossible. Put differently, Brazil’s mid-twentieth century flirtation with communism did not lead to much in the way of actual expropriation and nationalization. Having been purified rather than wholly consumed by government policy and macroeconomic forces, the best Brazilian entrepreneurs have been allowed to succeed, which is not to say that the Brazilian government didn’t pick favorites. To be sure, the Brazilian government was for many years more pro-business than pro-market. But, regardless of any favors that a particular business may have received in decades past, the current success of most any Brazilian business is more despite government policy than because of it.

The degree to which decades of seasoning distinguish Brazilian entrepreneurs from the majority of their emerging market peers became increasingly clear over the course of this past year. A surprisingly large fraction of successful companies in the developing world are run by operationally competent but financially unsophisticated individuals who want to grow at any cost. While a viable modus operandi for a time, this lack of financial sophistication invariably causes problems when the environment changes or bad investment opportunities present themselves. In the absence of a clear return on capital framework, these “growth at any cost” entrepreneurs eventually make low return on capital investments, and over long periods of time as a company’s return on capital merges with its return on incremental capital invested, they are unlikely to sustain superior returns. It is for this reason that we are so focused on superior businesses with superior managements.

Happily, “growth at any cost” is not a mantra that you’ll often hear in Brazil. Those Brazilian businessmen who levered up to accelerate growth are, for the most part, no longer with us. Absent as well, are entrepreneurs that don’t understand cost of capital. Instead, we’ve found a significant clumping of Brazilian entrepreneurs with a refreshingly sophisticated and creative approach to capital management. Many of them have an almost intuitive grasp for the way in which return on capital employed can act as a speed limit on their growth. They also have seen how quickly poor capital management or a weak competitive position can lead to failure in a challenging macroeconomic environment. These experiences, it should be noted, have had the attendant benefit of imbuing the average Brazilian corporate leader with a healthy dose of humility, an attitude lacking in a large swath of the developing world that still sees itself as destined for greatness.

For stock pickers such as ourselves who focus on the exceedingly rare combination of a superior business with great management trading at a low valuation, the Brazilian stock market’s year ago fire sale offered something of a momentary paradise. Even now, with the prices of Brazilian equities having more than doubled over the past year, we remain comfortable with our twenty plus percent Brazil weighting, and we would look to add to this figure in a pullback. Part of our comfort level with Brazil comes from the increasingly good protections accorded to minority shareholders there. While we’ve certainly come across numerous unscrupulous or just plain crooked Brazilian businessmen, we find that almost without exception they all recognize Western notions of transparency and governance as valid benchmarks, even if they themselves are not willing to adhere to them. This simple recognition that all shareholders are owners of a business is an acknowledgment that puts Brazil years ahead of Asia. The creation and success of the Novo Mercado—a section of the Brazilian Stock Exchange reserved for companies embracing good corporate governance practices—is a very definitive sign of the Brazilian mindset in this regard. Interestingly, no exchange in Asia has anything comparable.

With their strong banking system and seasoned entrepreneurial class, Brazil is in a perfect position to continue on a course of rapid development. All the Brazilian government has to do is make sure that running a business, not who you know, remains the key determinant for success. Of course, politicians being politicians can’t help but meddle. Furthermore, it seems Brazil’s politicians have proven immune to the humility that the private sector has internalized. Accordingly, the Brazilian government—in its infinite wisdom—has begun encouraging the creation of national champions that can become true multinationals. To this end, the government has permitted the merger of dominant local companies such as BM&F and BOVESPA, Itau and Unibanco, Totvs and Datasul—to list a few. Not only is the Brazilian antitrust agency not stopping these anticompetitive mergers, but the Brazilian government is actually lending the acquirers money at discounted rates to effect the mergers. Having benefited handsomely from our ownership of some of these newly minted monopolies, we are hard pressed to complain too loudly. That said, such obtuse policy makes us uncomfortable. While we’ve benefited in this instance, we have little confidence that our interests and those of the Brazilian government will always be so neatly aligned.

Shorting Sovereign Debt

“Western democracies, communistic capitalists, and Japanese deflationists are concurrently engaged in what may be the largest, global financial experiment in history.”[1] Indeed, the massive global monetary and fiscal policy response to the recent debt-deflation is unprecedented, and the dramatic reflation in asset prices in 2009 is most surely a function of these historic policy extremes. But what will be the longer term implications of this huge stimulus? While Equinox would not claim to be able to answer this question with precision, we do sense an appealing investment opportunity—the ultimate reversal of very low sovereign interest rates in highly indebted countries like the US and Japan.

Unlike most short positions, in the case of low yielding debt, simple arithmetic demonstrates an unusual and attractive asymmetry of risk and reward. For example, if the 1.3% yield on ten year Japanese government bonds (JGB) quickly dropped to its all time low of 0.43%, losses on a short position in this security would be a modest 8%. If, on the other hand, the ten year Japanese sovereign rate rapidly increases to “normal” pre-debt-deflation levels, this position would generate a 20%+ profit. Equinox started shorting long-dated JGB’s in 2003 at fractional interest rates, and we have maintained the position ever since.[2] A year ago, we did likewise with long duration US Treasury bonds when their yields were flirting with 40 year lows. Recently, we have increased both exposures.

In Japan and America, low government interest rates are coinciding with unprecedented government deficits and monetary stimulus. In this fiscal year, governments in America and Japan will each, on a net basis, borrow about 12% of their GDP (about the same as Greece)—and this on top of an already heavy debt burden. In Japan, net government borrowing will exceed government revenues for the first time, and, unless their economy recovers next year, they may see a similarly large issuance again. As if these amounts were not burdensome enough, both countries are considering further fiscal spending stimulus packages.

Japanese Government Fiscal Balance and JGB issuance (trillion yen)

| Year-End 3/31 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010(E) | 2011(E) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Gov Budget | 84.8 | 83.7 | 82.4 | 84.9 | 85.5 | 81.4 | 81.8 | 88.9 | 96 | 90-95 |

| JGB Issuance (net) | 30.0 | 35.0 | 35.3 | 35.5 | 31.3 | 27.5 | 25.4 | 33.2 | 53.5 | 44+ |

| Tax Revenue | 47.9 | 43.8 | 43.3 | 45.6 | 49.1 | 49.1 | 51.0 | 44.3 | 36.9 |

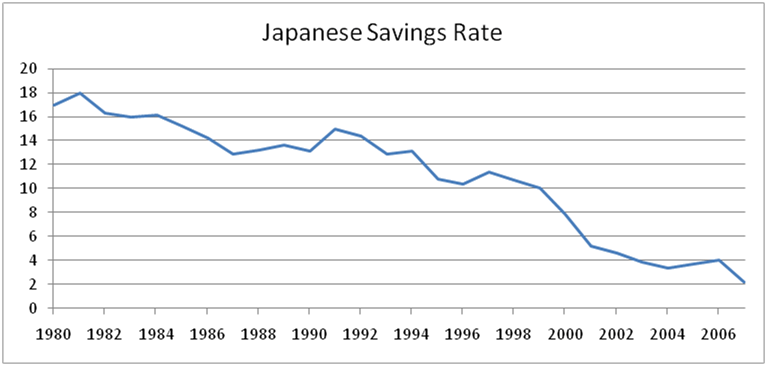

With Japanese rates lower than those in the US, despite the Japanese debt situation being more severe, we continue to prefer our JGB short position. Not only are Japanese rates the lower of the two, but the prospective deterioration in the Japanese government’s credit quality appears to be progressing even faster than it is here in the US. Continued very poor economic performance and an unwillingness to significantly cut spending all but assure a large supply of Japanese government bonds will be coming to market every year for the foreseeable future. Moreover, the pool of prospective liquidity to purchase JGBs is diminishing at an alarming rate as the aging Japanese population is saving much less than in the past. Surprisingly, Japanese now save even less than their American counterparts.

Of course with interest rates so low on Japanese debt currently, the debt service component of their government budget is none too onerous at this time. But, if rates rise meaningfully in Japan, debt service would commensurately increase and worsen the fiscal deficit further. Hence, it would appear that sovereign rates in Japan are unstable to the upside. With such limited risk, this position provides Equinox with a rare asymmetrically appealing shorting opportunity.

Equinox finds both countries curiously unconcerned about the decline of their governments’ balance sheets. Worrisome as it may seem for Americans, the Japanese seem even less focused on changing their spendthrift ways. Michael Zielenziger, in his fascinating new book Shutting Out the Sun, describes his recent study of what has gone wrong in the Land of the Rising Sun:

The Japan I encountered was unable to rejuvenate itself after a mysterious “lost decade” of financial failure and slowing growth. It seemed without the power or will to overhaul an ossified political system. Indeed, Japan systematically stifled widgetchange and resisted innovation … (p. 7, Shutting Out the Sun).

The recent announcement that the upper house of Japan’s legislature voted to reverse the privatization of the massive, corrupt national postal system, the most important reform of the Koizumi administration, is a good case in point. What’s more, the new governing party in Japan seems to be strangely lacking any sense of urgency about their country’s worsening budgetary dilemma. Japan’s sclerotic behavior, of course, adds to the likelihood of much higher domestic interest rates in the years to come.

Sincerely,

Sean Fieler

William W. Strong

END NOTES

[1] Hayman Advisors September 2009 letter

[2] Our actual position is in a swap not the cash bonds