Equinox Partners, L.P. - Q2 2005 Letter

Dear Partners and Friends,

The Fundamental Case for Gold

Many of the potential Equinox investors we meet have a negative visceral reaction to the idea of investing in the gold sector. While they no longer get up and walk out of our presentation as they did in the l990s, it is safe to say that the majority of them are still extremely skeptical about gold’s investment merits.

This ingrained skepticism, no doubt a product of gold’s two decade bear market, has prevented some from making the connection between gold’s recent rise and the large macroeconomic changes which have been developing since the late 1990s. It is no coincidence that gold’s long decline coincided with the spectacular performance of almost all financials assets, the insatiable appetite of foreigners for the American currency, and falling risk premiums in the developed world. That each of these long enduring trends has begun to reverse course, helps explain today’s growing investment demand for the yellow metal. We expect this demand will continue to rise as the asset management community, which is still very underweight gold, begins to key in on gold’s fundamental merits as a long-term investment.

If sustained, even a small increase in the demand for gold promises to force the price of the metal substantially higher. Our optimism about the possible extent of a further upward movement in the gold price is based on an important fundamental development in the gold industry - the long-term inability of mine supply and government sales to respond to growing demand. We will spend the balance of the letter focusing on this issue of supply.

Mine Supply

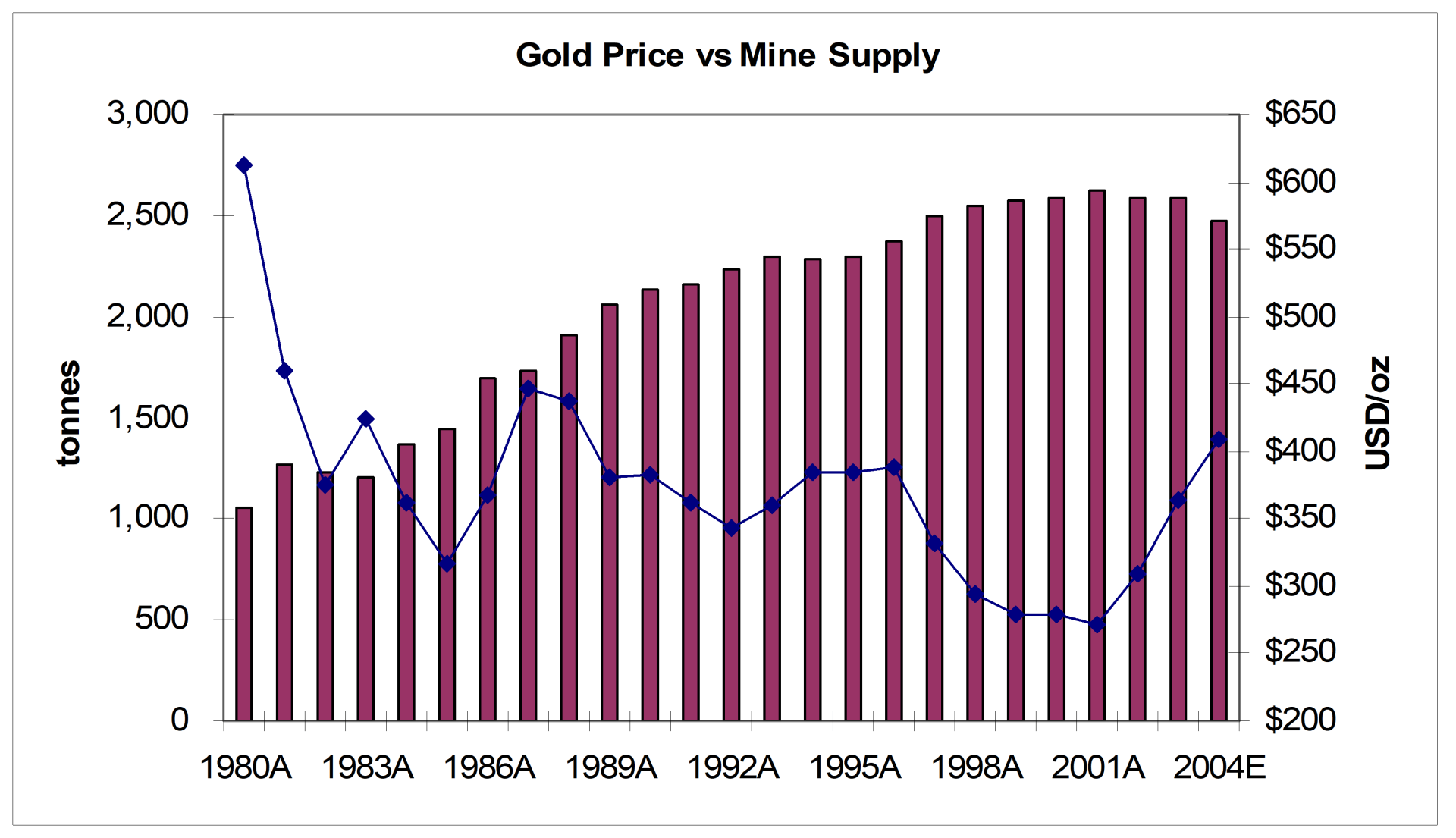

As the following graph makes clear, there is no discernable correlation between mine supply and price. In the late 1990s, when gold prices plunged, mine supply remained essentially flat. Similarly, mine supply has failed to respond to the recent rise in gold prices. Several factors explain the short-term price inelasticity of mine supply. Scaling up or down production at existing operations in the short-run is rarely an option because almost all mines are always being run at capacity to cover high fixed costs. Building a new mine requires years of geological and engineering work in addition to a large capital investment, and shutting down a mine also involves substantial costs.

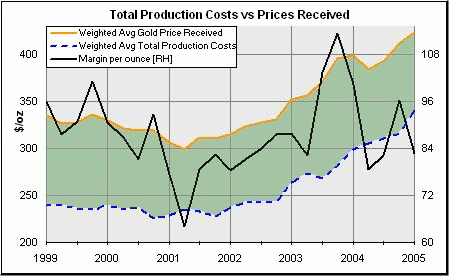

In the medium to long-run, the current price of gold is unlikely to elicit any increase in mine supply. As the below graph shows, higher operating costs have more than offset the effect of higher gold prices. In fact, the gold mining industry is currently suffering from a pronounced margin squeeze.

The two decade long bear market in gold led to structural underinvestment in the industry. During the late 1990s, capital spending was pared back, ore bodies were high-graded, and, perhaps most importantly, exploration budgets were reduced to the point that the industry as a whole was no longer replacing reserves. For many years, the industry has only been finding one ounce of gold for approximately every three it is producing.[1] As a result of this long-term underinvestment, the industry is left with very few economic ounces which can be quickly brought into production.

Government Sales

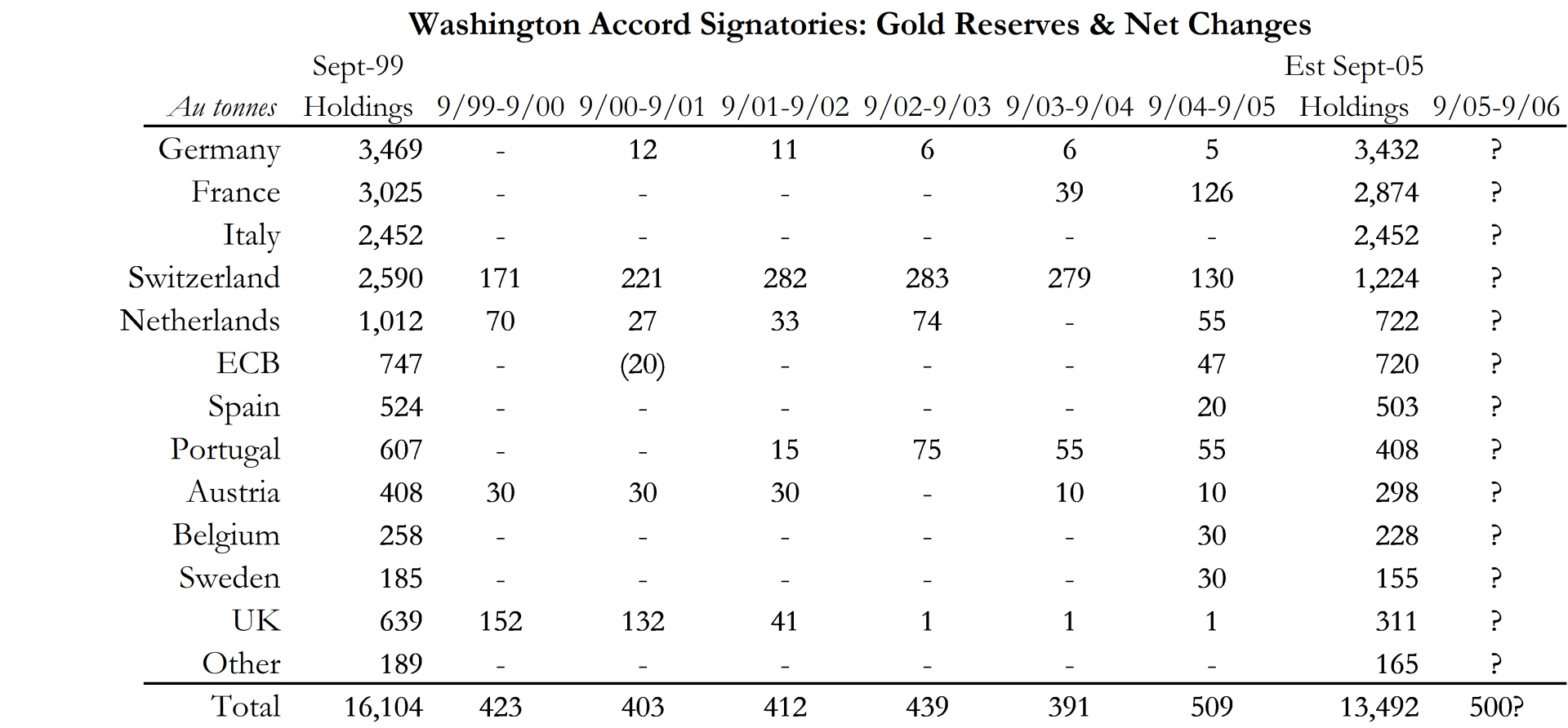

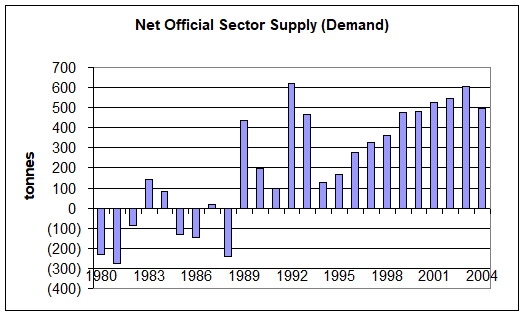

By the end of the 1990s, central banks had become such enthusiastic sellers of their gold holdings that they decided to sign an agreement, the Washington Accord, to keep their collective rush for the exit orderly. But, as the public record of recent years makes clear, central bank enthusiasm for gold sales has cooled markedly.[2] While the signatories to the Washington Accord did bring 500 tonnes to market over the past twelve months, the maximum allowed under the agreement, the sustainability of this high level of supply looks increasingly questionable. The Swiss, who have finished selling, supplied 130 of last year’s 500 tonnes, and none of the three remaining large holders, the French, the Germans, nor the Italians, appear eager to pick up the slack.

[1] Trevor Steel Study on gold exploration and production, 1990-2004. During the period, only 348 million new ounces were discovered while 1,165 million ounces were produced. The 348 million new ounces were discovered at an average finding cost $63 per ounce. Meanwhile, for each ounce of gold produced, only $19 was spent on exploration. Source: MineWeb (http://www.mineweb.net/events/conferences/2004/global_mining/320516.htm)

[2] On March 31st, 2004, the central bank of Switzerland announced that once it had completed its sales of 1,300 tonnes it would sell no more. On December 13th, 2004, the Bundesbank announced that it would not be taking up its option to sell 120 tonnes of Gold in the September 2004 to September 2005 period. On September 13th, 2004, Italy announced it had no plans to sell gold. On March 17th, 2004 President of the Banque de France, Christian Noyer, compared selling France’s gold to “selling the family jewels,” making clear France’s desire to sell as little gold as possible.

The current lack of enthusiasm on the part of key central banks for continuing their massive gold divestment program suggests that the renewal of the Washington Accord may have not even been necessary as it does not appear that the signatories to the 2004 agreement collectively want to supply the market with more than 500 tonnes per year. In this light, it is worth pointing out that the Washington Accord does not obligate any of the signatories to actually supply the gold; it only establishes a cap.

At the same time that central banks with sizable gold holdings are beginning to show a reduced appetite for gold sales, a few central banks with undersized holdings are beginning to buy gold. For more than a decade, gross central bank sales have been about the same as net central bank sales, which is another way of saying that no central banks have been buyers of gold. This is starting to change. Most notably, Russia and Argentina’s central banks have been recent buyers of gold. Depending on their size and persistence, central bank purchases could rapidly reduce the net quantity of physical gold supplied to the market by the world’s central banks.

Conclusion

Gold mining stocks have yet to react to gold’s improving fundamentals. The index of unhedged gold producers is still more than fifteen percent off of its 2003 peak, and many smaller gold mining stocks are down more than fifty percent over the last two-year period. During the past few months, we have been increasing our exposure to the gold sector. We expect the gold mining companies we own will perform well in a flat gold price environment, and should the price of gold rise further these holdings give us leveraged exposure to the upside.

Sincerely,

Sean Fieler

William W. Strong