Equinox Partners, L.P. - Q2 2004 Letter

Dear Partners and Friends,

Indonesia’s Banks

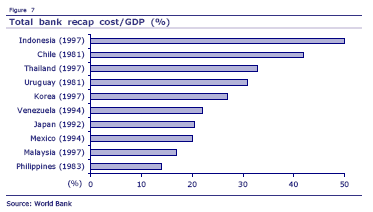

The Indonesian banking crisis of the late 1990s is one of the worst on record. In its wake, the government of Indonesia was forced to undertake the Herculean task of nationalizing and then re-privatizing a huge swath of corporate Indonesia. Key to the success of this effort was the recapitalization of the country’s banks. While the process was never pretty, it did create a well-capitalized and liquid banking system capable of strong growth in the years to come.

Well managed financially sound banks are not the normal outcome of financial system failures. More often than not, banks emerge from a crisis weakened and over-levered. To explain why requires a brief digression into the usual progression of banking crises.

Banks’ leveraged balance sheets leave little room for error. The loss of even a small percentage of bank assets can put a banking system in a precarious position; the loss of a larger percent of assets can set in motion a banking system crisis. Acutely aware of their inability to absorb sizable losses, banks often seek to conceal these losses rather than make public their impaired financial condition. Interestingly, governments often assist banks in this obfuscation. By allowing banks to understate the damage done to their balance sheets, governments hope to avoid calls for a costly banking system bailout.

When no amount of optimistic accounting can preserve bank solvency, governments find themselves forced to formally intervene to prevent a collapse. At this point, governments, almost always want to “fix” the problem while spending as little money as possible, as the funds expended are often viewed by the public as a taxpayer bailout of the bankers. Regrettably, a solution that understates the true extent of the damage invariably produces a structurally undercapitalized banking system. The resulting banks are, in turn, prone to cutting back on lending and widening interest margins as a means of completing the unfinished recapitalization process.

So why did Indonesia’s bank recapitalization succeed where so many other recapitalization programs have come up short? Simply put, Indonesia’s banking collapse was so severe that there was little opportunity to sugar-coat the truth. The Indonesian government had no choice but to socialize the losses and nationalize the banking system. Moreover, the controlling shareholders of the failing banks were so obviously corrupt so as to make their departure a precondition of any sensible solution.

The recent privatization of these recapitalized Indonesian banks has provided Equinox Partners with several exceptional investment opportunities. We have chosen to focus our fund’s investment in this sector on two exceptionally strong retail franchises, each of which has many years of rapid, highly profitable growth ahead.

Oil

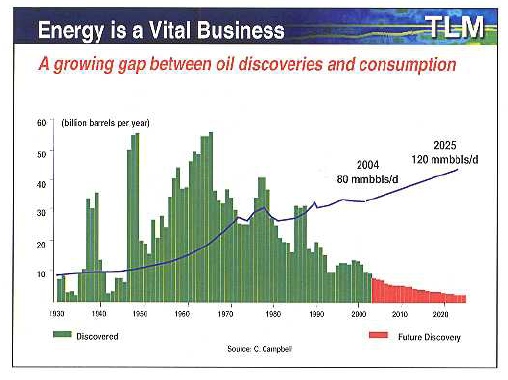

With the global economic recovery continuing apace and energy-thirsty Asia’s renewed growth, world oil production has reached capacity for the first time in decades. The prospect of even a modest 2%-3% per annum growth in world oil demand, on top of the burden of replacing declining production from existing fields, has experts raising the legitimate question of where increasing oil production will come from. As Jim Buckey, Talisman Energy’s CEO, recently stated the problem, “the world is consuming 30 billion barrels of oil a year and only finding 7 billion barrels.” (see below)

Years ago, when the epoch of expensive financial assets was still young, Equinox began studying out of favor hard assets which we hypothesized might be undervalued. Not surprisingly, we discovered that after a multi-decade bear market, some raw materials were selling well below the replacement cost of their reserves. Take oil for example. Lulled into complacency by many years when gasoline sold for less than generic bottled water at the local convenience store, it is easy to forget how scarce these subterranean hydrocarbon fuels, formed over hundreds of millions of years, really are. We at Equinox have long believed that the world’s inability to easily (cheaply) replace petroleum reserves would ultimately make this scarce resource considerably more valuable. This insight was made all the more valuable by our realization that the stock prices of some of the world’s best E&P companies were implicitly discounting extremely low energy prices into the distant future. Thus began our investment in the oil and gas sector.

Equinox’s first position in the Canadian oil patch was, in part, a function of our conviction that severely depressed Canadian natural gas prices would inevitably converge with those in the U.S. As this occurred in the late 1990s, we observed that gas supplies for all of North America would be stretched thin causing natural gas prices to appreciate to permanently higher levels continent-wide. Recently, we have increased our petroleum weighting towards oil because of its tight global capacity utilization. In addition, we have identified a few Canadian oil companies that have an imbedded “free call option” on higher than anticipated oil prices. This “optionality” derives from either an opportunity for large increases in high priced marginal production or a very long-term fixed cost production profile. Such stocks now represent almost half of our energy exposure. In the event oil prices find an equilibrium level that is higher than markets expect, Equinox should profit disproportionately.

What Price for Growth?

In early July, we increased Equinox’s already outsized short exposure to US technology shares. The point, eloquently made by Fred Hickey in his most recent letter that technology company revenues are currently running at a cool trillion dollars and reflect a maturing industry, has refreshed our enthusiam for shorting this sector. At almost a tenth of the US economy, technology companies simply cannot, as a group, merit the stock market valuation of their bygone glory growth days. But the memory of those heady days dies hard with American punters, as it did with growth stock investors in the early 1970s.

Microsoft’s decision to rationalize its capital allocation represents a watershed event in the growth cycle of the US technology industry. Here, Alan Abelson’s view closely parallels our belief. Of the company’s announcement that they are finally going to turn their massive cash hoard over to the shareholders, Abelson said:

“But it does suggest limits to opportunity—pure and simple. Gates and Ballmer couldn’t think of anything better to do with the money—and limits are anathema to the kind of investor who believes (absurdly but passionately) that certain chosen companies’ prospects are infinite and is willing to pay through the nose to own a piece of those illusory prospects.

It is not too much of a stretch, we submit, to see Microsoft’s dramatic action as an eloquent elegy of sorts for an era that stretches back a score of years during which computers dominated the high-tech landscape and nowhere more so than in the mind of Wall Street. That era obviously is coming to a close (easy there, Google fans; remember Netscape). For a technology, no matter how dominating and how pervasive is fated eventually to metamorphose into a commodity. And that’s increasingly the case with the technology that so animated stocks in the ‘Eighties and ‘Nineties, the technology in which Microsoft achieved preeminence.

This is not, let us make clear, a lament for high-tech. In terms of innovation and promise, high-tech’s alive and well. But Microsoft’s dividend bonanza confirms what has become more and more apparent for the past few years—that the next big new thing has yet to arrive. And when it does, it likely won’t much resemble the last big new thing.”[1]

Finally, a related thought about the proper valuation afforded growing businesses. We note that our Asian consumer branded companies, benefiting from accelerating disposable income in the region, are enjoying high single digit to low double digit unit volume growth. This growth, when combined with modest price increases, is enabling these companies to generate mid-double digit organic growth in revenues and earnings. In addition, with their very high returns on capital, these companies are left with substantial cash flow to add something more to their organic rate of growth. While we won’t digress into an academic argument about the proper price/earnings multiple that such growth deserves, we submit that it should be higher than the current seven. Over time, we expect earnings multiples on the Asian companies we own will expand to reflect that region’s long-term growth potential. Conversely, we expect earnings multiples on the large cap US technology companies we are short will contract to reflect that industry’s maturation.

[1] “Up and Down Wall Street”, Barrons, July 26th, 2004.

Sincerely,

Sean Fieler

William W. Strong