Equinox Partners, L.P. - Q2 2007 Letter

Dear Partners and Friends,

Watershed

It is the contention of Equinox Partners that the unfolding contraction of credit in the most leveraged and widely held asset class in the US is a watershed event. The impact of the incipient decline of domestic residential home values supporting $9.5 trillion of US mortgages to non-saving American households should not be underestimated. Moreover, the macro-economic consequences of this debt retrenchment in an economy with 340% debt to GDP, can only reinforce these bearish forces.

For some time, we have viewed the potential destruction of value resulting from a deleveraging of the American residential real-estate bubble as a significant shorting opportunity. Accordingly, last year we established short positions in home builders, mortgage originators, banks and mortgage insurers. We also positioned the partnership in the corporate bond market to benefit from the widening credit spreads that would likely result from a broad credit contraction. Recently, we added a short exposure to several investment banks which have leveraged exposure to the reversal of numerous financial trends--particularly the unwinding of the structured finance bubble.

More important than our effort to directly profit from the mortgage crisis through short selling, is our effort to profit from the consequences of the authorities’ efforts to stem the crisis. For starters, we strongly suspect that the policy response to the nationwide weakness in housing prices will prompt a further decline in the still overvalued US dollar. While the US dollar has already traded down against several major currencies, we would point out that these declines have yet to meaningfully impact Americans’ propensity to live beyond their means, and consequently America’s foreign debt position has continued to worsen. While this argument is certainly well worn, the US dollar, nevertheless, remains at an unsustainably high level.

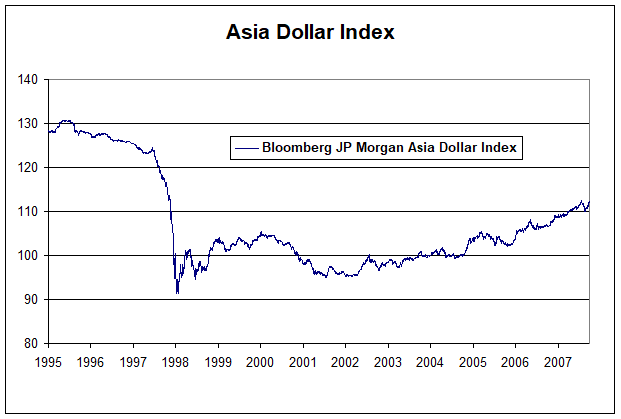

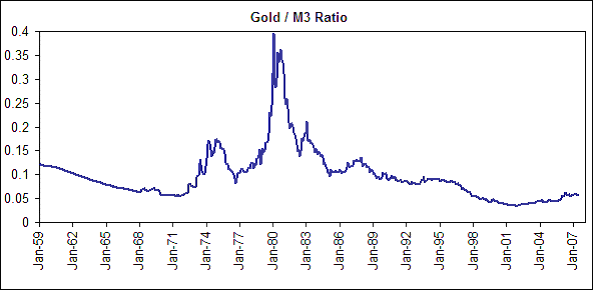

It is not exactly news that Equinox maintains a long-term bearish view of the dollar. This perspective has helped our performance during the post-millennium decline of the greenback. Though we’ve had no direct exposure to the almost doubling of the Euro, the commodity producers we own have enjoyed a significant tailwind from the dollar’s decline relative to gold and oil. America’s currency has now fallen by almost two thirds from its highs versus gold and about three quarters versus West Texas light sweet crude. The dollar’s performance relative to Asia’s currencies has been another story. In a successful effort to sustain their countries’ dominant competitive export positions, Asian central banks have pursued a policy of artificially supporting the US dollar. Consequently, Equinox’s gains from FX appreciation on Asian stocks have been modest to date.

Going forward, we expect the trend line in the above graph turn up meaningfully. What, after all, will the Far-Eastern neo-mercantilists do in the face of the Fed’s new campaign to reflate America’s economy? More to the point, it is hard to imagine that Europeans will tolerate further appreciation of the Euro while allowing Asian central banks to continue to hold down their own currencies. While we cannot predict the exact outcome of these highly politicized decisions, we believe our portfolio is well aligned with the dominant underlying economic forces now at work. And, we expect, the one monetary asset that is not a liability of any nation state, namely gold, to finally shine in the environment of competitive devaluations likely to ensue to in response to the ongoing credit contraction.

Structured Finance: The “Wizard of Oz” Meets the Credit Markets

What mathematical alchemy of structured finance transformed risky mortgages into high grade securities? This question has perplexed Equinox for years as we pondered the accelerating ascent of American house prices. Now, global skepticism about the same question is wreaking havoc in financial markets all over the world.

Though not experts in collateralized securities, we suspect the transformative arithmetic in question involves the skewing of cash-flow between security traunches combined with the assumption of ever rising US house prices. While American houses have appreciated historically, the investment banking and rating agency “wizards” who designed these structured securities appeared to have ignored an important element in their computer modeling – the self-reinforcing nature of their own actions. In other words, by making ever more expensive houses “affordable” they drove up prices to a level where the debt service was unsustainable. In their models, ever appreciating assets could at least be sold for enough profit to ensure the creditors’ repayment. But now, like the classic 1939 film, the bear market in US home prices has exposed the “wizards” as mere mortals behind the controls of impressive machines.

The complex internal structure of these securities and the non-transparent assumptions underlying their rating models has made them virtually impossible to analyze and forced investors to blindly rely on these securities’ credit ratings. However, with the credit rating agencies now thoroughly discredited, the value of the entire asset class is in doubt. It is deeply ironic that the very opacity that made the issuance of these securities possible, now makes the fearful contagion of their liquidation inevitable.

Of course, US residential debt is only one piece of the “Land of Oz” (collateralized debt) pie. A large volume of commercial mortgages and LBO financing has also been ‘sliced and diced’ into structured obligations. We can only imagine the actual credit performance of these securities if the US economy does not conform to the undoubtedly rosy assumptions built into these structured vehicles. Perhaps the devastation wrought by the “Wizard of Oz” financial geniuses is only in its opening phase.

The most troublesome variety of counterparty risk invariably originates with a firm of superior reputation. Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM) is a perfect example. Investors and counterparties alike, awed by LTCM's principals, failed to ask tough questions and thereby permitted the leverage that made LTCM’s eventual collapse so spectacular. In the nine years since LTCM’s demise, no hedge fund, no matter how lofty the reputation of its principals, has been able to escape the careful scrutiny of its counterparties. The market is simply too well schooled in hedge fund fragility. On account of the caution with which counterparties now treat hedge funds, we would be surprised if hedge funds, even highly levered ones, are at the center of the next big counterparty problem. We suspect that the truly problematic counterparty risk is lurking elsewhere in the financial system, somewhere with opaque balance sheets, aggressive leverage, and the arrogance and reputation to avoid answering tough, pointed questions. Our candidate is the investment banks.

The opacity of these firms is easily observable. One needs only to download a 10-K and dig in, footnotes first. Even if you are familiar with the alphabet soup of financial entity accounting, which is to say that you know your VIEs from your QSPEs and have a firm grasp on SFAS157, you’ll find a lot of information but not the information you need to judge these firms’ credit worthiness. In May of this year, at the end of a long conversation spent reviewing a particular investment bank’s footnotes, the company representative with whom we were speaking conceded what we’d already concluded: that the net exposure to various asset classes could not be deduced from the material provided. No amount of financial statement analysis would tell us what net exposure this particular investment bank had to structured product residuals, high yield debt, or bridge financing. The information simply wasn’t there. We were left, in the words of this company representative, to trust the firm’s strong culture, a shockingly arrogant comment from such a highly levered financial firm.

If, as we suspect, investment banks do pose a significant risk to their counterparties, many of whom are hedge funds, this is indeed a great irony, as the current thinking is that hedge fund failures pose a risk to investment banks, not visa versa. Other managers with whom we’ve spoken about this issue are largely dismissive of the potential risk. Were a major investment bank to become insolvent, they reason, the shareholders and maybe even general creditors would be punished, but the government would step in to protect the clients and other counterparties. The alternative is simply too catastrophic to countenance. Even we will admit that given the Fed’s track record of intervention over the past two decades, the US government could be seen as having had guaranteed the performance of the major investment banks as counterparties. Even so, we see no reason to test this guarantee.

At Equinox Partners, we’ve long taken a deliberate approach to counterparty risk management, carefully analyzing prospective counterparties and choosing to distribute our exposure across several firms if none stands out as a materially better risk. This past quarter, we took the additional step of segregating our custody assets from our prime brokerage assets. As we employ only modest amounts of leverage, we've been able to move a meaningful fraction of our long securities into a ring-fenced bank custody account at Northern Trust. While no account is completely free of counterparty risk, this, we believe, is as close as it comes. To the extent that we sell short and invest on margin, we will continue to hold a significant portion of our portfolio at Goldman Sachs and RBC. That said, the fund’s counterparty risk is now limited to a minimum given the portfolio structure.

Sincerely,

Sean Fieler

William W. Strong